Population growth rates by country (personally I think the color scale should be inverted so that red shows higher growth rates). This map is from 2021, but the story is largely the same today. Image via Our World in Data.

Before you start reading, open worldometers.info and take a screenshot (this will give you the world population right now; we’ll come back to it later).

Our world is facing enormous environmental challenges. Climate change is roaring forward at a terrifying rate, we are experiencing the 6th mass extinction, and natural resources like water are becoming increasingly scarce in many parts of the world. Humans are the root cause of these issues, but there is often a debate about whether we are causing them through overpopulation (i.e., too many people using resources) or overconsumption (i.e., too many resources being used per person). The reality is that both factors are occurring.

It is beyond question that we are overconsuming. Humans, especially those of us in heavily industrialized countries like the USA, use a truly extraordinary number of resources. Our society is unconscionably wasteful, and we need to take enormous steps to move away from fossil fuels, reduce food waste, reduce plastic waste, minimize land use, and, in general, move away from our disposable society and towards one that is more sustainable.

So, for the sake of this post, I’m going to largely take the overconsumption side of things for granted and focus, instead, on the overpopulation side, because this is usually where I find contention. In other words, at least in my experience, most people who argue that we are overpopulating also fully acknowledge that we are overconsuming and need to reduce consumption; whereas many others argue that the issue is entirely overconsumption and we shouldn’t be talking about overpopulation.

I am going to argue that overpopulation actually is a real issue, but there is a ton of nuance that has to be included when discussing that topic. So before sharpening your pitch forks, please hear me out. Also, as you read through this, I want you to keep the following central thesis in mind: almost all (possibly all) environmental crises would be easier to solve if there were fewer people on the planet.

Important clarifications

This topic often spawns lots of red herrings about eugenics, China’s one child policy, and other political topics. So let me be clear at the start that I am simply discussing the problem, not the solution (other than some very broad comments and advocation for personal actions). This post is not an argument for eugenics or any government actions to control the population size. Likewise, when I say that we need to rapidly reduce or even reverse the population growth rate, I am talking about slowing the rate at which we add new people to the population (birth) NOT the rate at which people are removed from the population (death). So please spare me your essays on genocide and eugenics; that’s not what I’m talking about here. I am simply describing the problem. The fact that some people have proposed unethical solutions to the problem does not mean that the problem isn’t real.

What the “overconsumption only” argument gets right

Next, I want to acknowledge that those who argue that we shouldn’t be talking about overpopulation do have some good points, but addressing them simply requires nuance, rather than avoiding the topic of overpopulation all together.

First, as I already acknowledged, overconsumption is an enormous problem, and there would be space and resources for a lot more people if we lowered our consumption rate (see section on carrying capacity later). I 100% agree that we need to massively reduce consumption and waste.

Second, a key problem with blanket statements like, “there are too many people on the planet” is that those statements ignore the fact that neither consumption rates nor population growth rates are equal across countries. Indeed, they are inversely correlated, meaning that countries with disproportionately high consumption rates tend to have very low population growth rates (i.e., heavily industrialized countries), whereas populations with very low consumption rates tend to have the highest population growth rates (i.e., impoverished countries). Thus, if you aren’t careful and don’t include appropriate nuance, the overpopulation argument can easily place the blame on the wrong group of people and even become racist.

For example, the USA has a small population growth rate of 0.6% per year (from 2013-2022; worlddata.info) and only roughly 4.2% of the world’s total population (worldometers.info), yet it produces a full 14% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions (statista.com). India, meanwhile, has an average growth rate of 1.14% per year (2013-2022) and 17.8% of the world’s population (worldometers.info), yet it only produces 7% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions (statista.com). Put another way, India has twice the population growth rate and over 6 times the population size of the USA, yet it produces half the total greenhouse gas emissions compared to the USA!

Things are even worse when we start looking at the continent of Africa, which has many of the highest growth rate countries, most of which produce minuscule amounts of waste compared to other countries.

To put all of that in its simplest terms, the countries that are contributing the most to the growth of the human population are also generally the ones that are using the fewest resources (especially per capita). So, if you simply say that we have an overpopulation problem, you run into trouble because the countries that are “overpopulating” aren’t actually the ones that are contributing the most to our current environmental catastrophes. This is where we need a lot of nuance, which is what I will try to build throughout the remainder of this post.

Carrying capacity

In this section, I want to explain the fundamental reason why I, as an ecologist, think we have to talk about overconsumption and overpopulation simultaneously. Namely, they are two sides of the same coin that are intrinsically linked.

To understand what I mean by that, we need to understand the concept of carrying capacity. This is the number of organisms of a given species that a given area can sustain. Carrying capacity is determined by both the amount of resources present and the rate of consumption. Thus, overpopulation, in strict ecological terms (though see later section), occurs when the population size exceeds the carrying capacity.

Have you spotted the catch there? Carrying capacity is determined by consumption rate, which means that “overpopulation” is determined by the consumption rate, but also, “overconsumption” is determined by the population size.

Stated another way, if a field of cows exceeds its carrying capacity, you could describe it either as “there are too many cows given their consumption rate” (overpopulation) or “cows consume too much to maintain this population” (overconsumption). Both are accurate descriptors of the situation. To be fair, that analogy is a bit strained because we don’t typically think of cows as overconsuming, but mathematically, those two situations are the same.

Now let’s apply that to humans, and to simplify things, let’s focus on countries like America that have very high consumption rates. I do not think that the per capita consumption rate of America is sustainable given the population size, which is the exact same thing as saying that I do not think the current population size is sustainable given the per capita consumption rate. Those statements are equivalent.

To put that another way, we could sustain this many people if we consumed less, or we could sustain this per capita rate of consumption if the population size was smaller.

“Overpopulation” is determined by consumption rate, and “overconsumption” is determined by population size. You cannot simplify things to one or the other because they are inherently relative to each other.

Understanding this relationship is critical for developing appropriate solutions to our problems. Both factors are at play, and both need to be addressed, rather insisting that only one of them is a problem.

What does “overpopulation” mean for humans?

This is another point at which we need to inject nuance. As described above, ecologically, “overpopulation” means that a population has exceeded that area’s carrying capacity. So in strict terms, “overpopulation” for humans would mean more people than the planet can actually sustain. This is what Malthus was famously concerned with, and proponents of the “overconsumption only” argument often argue that there have been countless estimates of earth’s carrying capacity that have proved to be wrong. That’s not a great argument, in my opinion, because there is a carrying capacity for earth. The fact that we haven’t done a great job estimating it (largely because technology keeps saving our butts) doesn’t mean that one doesn’t exist.

More importantly, I think that this is something of a strawman, because when conservationists like me talk about overpopulation, we usually aren’t strictly referring to the maximum number of people possible. Rather, we are referring to the number of people that can be sustained while still preserving biodiversity. In other words, we could fit a lot more people on this planet if we cleared all the forests, dammed all the rivers, and mined every last resource. Sure, that would cause lots of other issues, but the total number of people we could sustain would go up. However, we would have destroyed all the natural wonder and beauty of this planet, and that is not a situation I want.

I want a sustainable future where we still have massive tracts of rainforest, pristine coral reefs, plains and savannas, untouched deserts full of bizarre lizards, crystal clear rivers, and national parks that stretch to the horizon. I want to conserve all the unique and wonderful plants and animals that call this planet home. I want the splendor of this pale blue dot to persist, and the simple reality is that every additional human makes that goal harder.

Even people who live as sustainably as possible are using resources. Even if you live in a modest house, use entirely renewable energy, and grow your own food, there are still resources that had to be mined to make your solar panels, wind turbines, etc., and you are still using land that would be better for biodiversity if it has been left in its natural state. Further, if you are reading this, then you must have a computer or smart phone which includes components that were shipped from all around the world. Likewise, if you go to the doctor, you will burn through a bunch more resources from medical waste (syringes, medicine bottles, etc.) as well as increasing the burden from manufacturing and shipping those supplies.

Resource usage is inescapable, and it is not inherently a bad thing. All organisms use resources, but the fewer organisms there are, the fewer resources need to be used. This is an unavoidable fact. Even if we all agree to drastically reduce our resource usage, we would still be placing a huge burden on the earth, and that burden would be reduced with fewer people.

How much luxury are we willing to give up?

Let me state again that overconsumption is a huge problem, but the question becomes, how much are we actually willing to give up? It’s easy for those of us in places like America, Europe, and Australia to look at other countries with very low resource usage and high population growth rates and say, “see, if we just reduced our consumption to match those countries, we wouldn’t have a population problem.” The reality, however, is that very few people actually want that. A large part of why those countries consume so little is because they are impoverished. They don’t have massive food waste because they have so little food that they cannot afford to waste it. They don’t have massive medical waste because they don’t have good access to medicine. They don’t have massive greenhouse gas emissions because they don’t have reliable electricity and/or can’t afford all the cars, electronic appliances, and gizmos that we take for granted.

So how much comfort are we actually willing to give up? Are we willing to give up a car (often multiple) per household? Based on the extraordinary number of unnecessary gas guzzlers I see on the road, I highly doubt it. Are we willing to use the same TV, computer, phone, etc. for decades rather than replacing them semi-annually? I doubt it, and even if we were, they aren’t manufactured in a way that makes that plausible. Likewise, while food waste is serious problem, a large part of the food waste comes from us demanding a high quality in our food, which means that old products get disposed of if they didn’t sell, and only the highest quality produce goes to market. Are we willing to reduce those standards, and what will the cost of that be in terms of human health?

I could go on, but I think the point is clear: while we should do everything we can to reduce resource usage, there is a limit to how much we can reduce it without reducing our standard of living. Again, that is not necessarily a bad thing. There is nothing inherently wrong with wanting a comfortable life that makes use of all our modern technological wonders, but, that standard of living inherently comes with a high environmental burden, and we need to seriously consider how many people we can sustain at that standard while still maintaining biodiversity.

Increasing industrialization

Something of the inverse of what I have just described for heavily industrialized nations (low population growth rates) is happening for less industrialized nations (high population growth rates). Namely, they are becoming more industrialized and, in the process, are using more resources per capita. Here again, that is not inherently a bad thing. That increase in resource usage is largely due to an increased standard of living, and most (I hope all) of us would like everyone to be able to enjoy a high standard of living. I want everyone to have access to modern healthcare, reliable electricity, and modern amenities (assuming they also want that access), but this is something we need to think about as we plan for a sustainable future.

Those rapidly growing populations will, hopefully, have access to a high standard of living in the near future, but even if that is done as sustainably as possible, it will still require a large increase in resource usage. In other words, these large, rapidly growing populations have low per capita resource usage now, but that is almost certain to change in the near future. Not all of that change is bad, but is there room for that expansion (while maintaining biodiversity) given how many of us currently enjoy such a high level of resource usage? Unless something drastically changes, I don’t think so, which is a problem. There are too many of us consuming too much for rapidly growing populations to increase their resource usage without it resulting in environmental catastrophe.

It is a complex problem, and our population size, our consumption rate, their growing population size, and their likely future consumption rate are all a part of it. Again, to be clear, I am not blaming anyone. I am simply describing the reality of the situation.

Land use

An additional problem with the “overconsumption only” argument is that it often focuses on the inverse relationship between population growth rates and things like greenhouse gas emissions, while ignoring other problems such as land use. This is an overly simplistic view. Due to their high growth rates, many countries are becoming extremely densely populated, which inherently necessitates clearing land for development and agriculture. Unfortunately, many of these countries are also biodiversity hotspots, and natural areas inherently have to be sacrificed to accommodate those people. Keep in mind that habitat loss is hands down the leading cause of biodiversity loss.

Let’s keep using India as an example, for a minute. It has truly incredible biodiversity, but due to its historically high population growth rate, it now has a density of nearly 500 people per square kilometer (>1200 per square mile; worldometers.info). The USA, by contrast, has a mere 37 people per square kilometer (96 per square mile; worldometers.info). That high density in countries like India inherently requires clearing a lot of land, and, tragically, that land is some of the most biodiverse in the world.

Likewise, I had the opportunity to visit the Philippines last year, which had an average annual growth rate of 1.78% from 2013-2022 (worlddata.info) and now has a population density of nearly 400 people per square kilometer (>1000 per square mile; indexmundi.com). That’s an order of magnitude higher than the USA. I visited multiple islands while I was there and was consistently astounded by the population density and how much forest had been cleared. My wife and I went on a birding tour, and talking to our guide about the state of bird conservation there was truly alarming. Repeatedly we’d ask about a particular species, and he’d tell us that he used to have a reliable spot for them, but now that location has been cleared and he rarely sees that species anymore.

We are losing biodiversity incredibly fast, and clearing land for expanding human population is a huge part of that. We cannot afford to ignore what is happening for the sake of political correctness. To be clear, I’m not blaming people in countries like the Philippines or India for clearing so much land, what else are they supposed to do when they have that many mouths to feed and people to house and employ? Of course, they have to clear lots of land. Resource use is not inherently a bad thing, and they still use less land per capita than those of us in countries like the USA. My point is simply that even though they use far fewer resources and less land per person, their rapidly growing populations still have an enormous impact on the environment. That’s an issue we have to acknowledge if we are going to plan appropriate conservation measures.

Note: I also want to make it clear that those of us in heavily industrialized countries are also playing a huge role in habitat loss in other countries due to our insatiable lust for things like palm oil.

“But growth rates are slowing down!”

A final argument I often hear levied against the overpopulation argument is that the world’s growth rate is slowing, and even rapidly growing countries are experiencing reduced growth rates.

This is true, but is not the same thing as saying that we won’t overpopulate (or haven’t already). There are currently over 8 BILLION people on this planet. Most projections suggest that our population won’t truly level off until well past 10 billion. Two billion extra people is an enormous change! That’s a 25% increase in population size! Which also means a 25% increase in the minimum number of resources needed. In short, it is not slowing nearly fast enough.

Further, as a conservation biologist and ecologist, I’d argue that we are already grossly overpopulated if we want to maintain biodiversity. The 6th mass extinction isn’t something that is going to start in the future. It is something that is happening right now, and adding another 2 billion people is not going to help. We need to be going the other direction. Conserving this wonderful, beautiful planet and all its natural treasures would be so much easier with a couple billion fewer people.

Further, while the growth rates are highest in impoverished countries, that 0.6% increase in the USA is not a small thing. As I am writing this, the USA population increases by a net of 1 person every 24 seconds (i.e., after accounting for births and deaths). If it took you 20 minutes to read this post, then there are (on average) 50 more people in the USA now than there were at the start. Each day, there are 1728 more people! Now, think about the amount of resources that each person in the USA uses. Think about the cars they will own, houses they will build, clothes they will wear, cell phones they will use, fuel they will consume, food they will eat, etc. Then tell me with a straight face that adding 1728 more people per day isn’t a problem.

I find it really difficult to explain the true scale of environmental devastation that is currently occurring to people who don’t work in conservation. The rate of species loss we are experiencing keeps me awake at night with grief, and saving those species would be so much easier if there were fewer people. Fewer people would mean more land that could be left in its natural state, fewer resources that need to be mined, less food that needs to be grown, fewer buildings that need to be built, fewer flights, less intercontinental shipping, less energy that has to be produced, fewer products to manufacture, less waste going into landfills, fewer animals being harvest from the ocean, and fewer emissions being produced. Essentially every environmental problem is easier to solve with fewer people.

Reopen that link that I posted at the start of the article and compare the world population now with the world population in the screenshot you hopefully took. Unless you are an incredibly fast reader, there are several thousand more people than there were at the start. We are still growing at a truly alarming rate.

What do we do?

As I said earlier, I’m not going to give any specific solutions or governmental options, I’m mostly trying to raise awareness about the problem, but I do want to talk about some general broad strokes for a minute.

First, we need to reduce our consumption and waste. This is really beyond question. There are lots of things we can do to live more sustainably without substantially lowering our standard of living, and it is inexcusable for us not to making those changes. Let’s be 100% clear that those of us in affluent, heavily industrialized countries are responsible for the vast majority of our current environmental crises, and the people in the countries that are the least responsible are bearing the brunt of the negative consequences of our actions.

Second, I think we should help impoverished countries to grow financially and industrially, while trying to help them do so in a sustainable way. Beyond ethical reasons, helping them to gain access to better healthcare and a clean energy grid is actually a good investment in all of our futures, because as countries become more industrialized and gain better access to healthcare, they tend to have fewer children (voluntarily) and the population growth rate levels off. The sooner that growth rate levels off, the fewer people there will be and the more resources will be available.

Third, those of us who are already in industrialized countries should halt, or better yet, invert our growth rates to make room for those growing populations. Again, I’m not talking about any government action (that’s a separate topic). Rather, I am talking about individuals choosing to forgo having children (or at least having fewer children). This is where the nuance is so important. A single child born in a country like America is far more damaging to the environment than a single child born in a country like India or many African nations.

“Overpopulation” is relative to resource usage. So simply looking at growth rates doesn’t tell the whole story, and a small growth rate in a heavily industrialized country is far worse than a large growth rate in a comparatively unindustrialized country.

As explained earlier, even if you live as sustainably as possible, you will still use resources. So, assuming that your child will have the same resource usage as you, having a child essentially doubles your impact on the earth (or increases it by 50% if you want to lay some of the blame on your partner). The simple reality is that, for most of us, the single best thing we could do for the planet is to forgo having children. Eating locally grown food, using renewable energy, driving a small car, and making fewer transcontinental flights are all good, but they pale in comparison to the lifetime resource usage of a single human being. Lest anyone accuse me of hypocrisy, I will note that my wife and I decided not to have any children, and environmental concerns were a big part of that decision.

The fundamental point I am trying to make is simply that both population growth rates and resource consumption rates are part of the problem, and we need to acknowledge that in order to develop appropriate solutions. For example, yes, we need to reduce our level of food waste, but imagine if, in addition to doing that, we also had fewer mouths to feed (or at least stopped generating as many new mouths). Think how much more land could be set aside for conservation if we did both instead of insisting that only one of them was a problem. The same is true for essentially any environmental topic. Yes, we should switch to renewable energy, but renewable energy still has environmental costs (e.g., highly destructive mining practices and large areas of land for solar farms) and we would have fewer of those costs if there were fewer people who needed that energy. We are in the middle of a sixth mass extinction, and we cannot afford to ignore a huge part of the problem.

Essentially every environmental crisis is easier to solve if there are fewer people, and the fewer people there are, the more biodiversity we can maintain without having to sacrifice our standard of living.

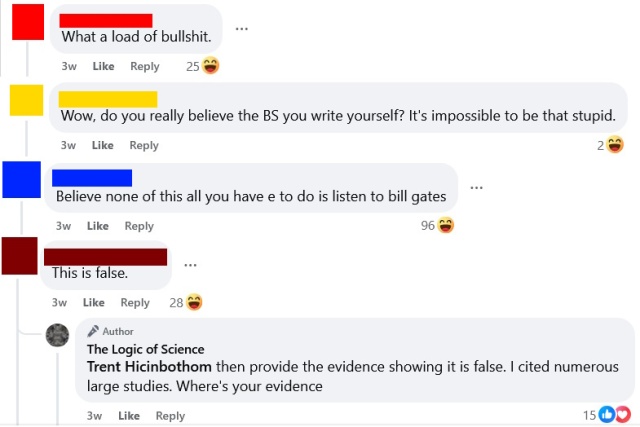

In recent conversations on this page, I have been struck by just how intellectually lazy science-deniers usually are. This is hardly a novel observation, but I think it bears discussion. I also want to note that this sort of lazy thinking is common in politics and countless other topics, and it is very easy to fall into these bad habits. Critical thinking is a skill, and like most skills, it requires practice. Being well-informed takes hard work. Blind adherence to biases and preconceptions is much easier than rigorous fact-checking and serious contemplation. We are all prone to cognitive biases, but if we want to have rational views based on evidence and logic, then we need to acknowledge those tendencies and fight against them. We need to be humble and acknowledge the limits of our personal knowledge and be intellectually diligent and honest. Blind denial of any information you don’t like is easy and seductive, but it is not rational or intellectually rigorous.

In recent conversations on this page, I have been struck by just how intellectually lazy science-deniers usually are. This is hardly a novel observation, but I think it bears discussion. I also want to note that this sort of lazy thinking is common in politics and countless other topics, and it is very easy to fall into these bad habits. Critical thinking is a skill, and like most skills, it requires practice. Being well-informed takes hard work. Blind adherence to biases and preconceptions is much easier than rigorous fact-checking and serious contemplation. We are all prone to cognitive biases, but if we want to have rational views based on evidence and logic, then we need to acknowledge those tendencies and fight against them. We need to be humble and acknowledge the limits of our personal knowledge and be intellectually diligent and honest. Blind denial of any information you don’t like is easy and seductive, but it is not rational or intellectually rigorous. The aforementioned article took me a long time to write. I wanted to be thorough and present a fair and honest representation of the scientific evidence. So, I spent many days reading the literature, fact-checking, and making sure that what I was saying was correct. I cited roughly 50 peer-reviewed articles (mostly meta-analyses and systematic reviews) and read numerous others while preparing that post.

The aforementioned article took me a long time to write. I wanted to be thorough and present a fair and honest representation of the scientific evidence. So, I spent many days reading the literature, fact-checking, and making sure that what I was saying was correct. I cited roughly 50 peer-reviewed articles (mostly meta-analyses and systematic reviews) and read numerous others while preparing that post.

I want to briefly discuss a logical fallacy that is surprisingly common, despite being so obviously absurd. I suspect that most people committing this fallacy do so without ever actually contemplating what they are saying, and it is my hope that discussing this fallacy will help people to both spot and avoid it.

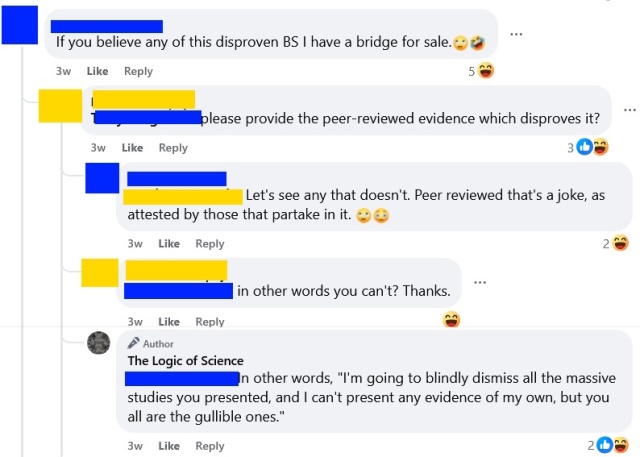

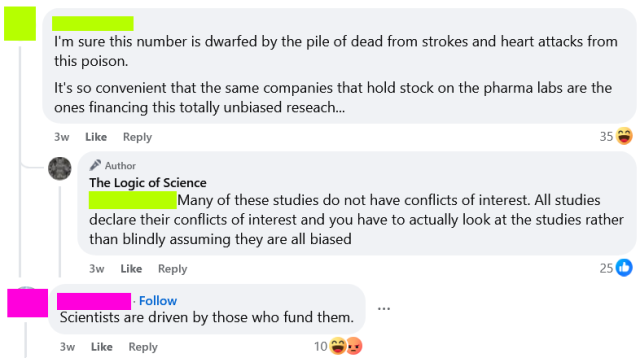

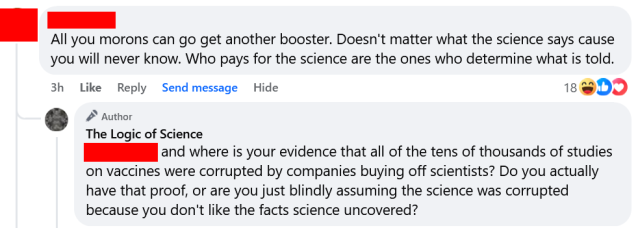

I want to briefly discuss a logical fallacy that is surprisingly common, despite being so obviously absurd. I suspect that most people committing this fallacy do so without ever actually contemplating what they are saying, and it is my hope that discussing this fallacy will help people to both spot and avoid it. Yesterday, I posted the fairly innocuous image above on the TLoS Facebook page, and the results were both fascinating and horrifying. Numerous people took time out of their day to embarrass themselves by doubling down and attacking fact-checkers, often with truly deranged comments that were totally detached from reality and clearly illustrated why fact checking is so important. Further, multiple people (all on one side of the political aisle) incorrectly interpreted this as a political post, a response which is delightfully revealing. Given the responses that this post engendered, I think it will be instructive to clarify several points and discuss some of the comments. This is hardly the first time that I have written about fact-checking, and you can read a much longer post on it

Yesterday, I posted the fairly innocuous image above on the TLoS Facebook page, and the results were both fascinating and horrifying. Numerous people took time out of their day to embarrass themselves by doubling down and attacking fact-checkers, often with truly deranged comments that were totally detached from reality and clearly illustrated why fact checking is so important. Further, multiple people (all on one side of the political aisle) incorrectly interpreted this as a political post, a response which is delightfully revealing. Given the responses that this post engendered, I think it will be instructive to clarify several points and discuss some of the comments. This is hardly the first time that I have written about fact-checking, and you can read a much longer post on it  First, I want to deal with the strawman that I was suggesting that people should blindly believe fact-checkers (see a selection of such comments to the right). I have never said anything of the sort, and, in fact, the original post wasn’t about professional fact-checkers at all. Rather it was about individuals checking facts before believing something.

First, I want to deal with the strawman that I was suggesting that people should blindly believe fact-checkers (see a selection of such comments to the right). I have never said anything of the sort, and, in fact, the original post wasn’t about professional fact-checkers at all. Rather it was about individuals checking facts before believing something. Let’s look at one case that I found particularly amusing. After a general statement against Snopes, the person in red doubled down with the claim that Snopes had testified before Congress that their fact checks were actually opinions (note that they did not specify Snopes, but that was the subject being discussed, and the “the” appears to be a typo for “they”). This would have been a great place for red to fact-check before posting, because Google failed to reveal any such testimony, and when pressed for evidence that such a confession had taken place, red posted a NY Post

Let’s look at one case that I found particularly amusing. After a general statement against Snopes, the person in red doubled down with the claim that Snopes had testified before Congress that their fact checks were actually opinions (note that they did not specify Snopes, but that was the subject being discussed, and the “the” appears to be a typo for “they”). This would have been a great place for red to fact-check before posting, because Google failed to reveal any such testimony, and when pressed for evidence that such a confession had taken place, red posted a NY Post  Finally, let’s briefly turn to politics for a second, because when I made my initial post something fascinating happened. The post was not even remotely political. Nevertheless, a bunch of people came crawling out of the woodwork to claim that it (or fact-checking more generally) was part of some leftist agenda. That is, in my opinion, a fascinating and hilarious self-own. It is fundamentally an admission by these people on the right that the facts are not on their side.

Finally, let’s briefly turn to politics for a second, because when I made my initial post something fascinating happened. The post was not even remotely political. Nevertheless, a bunch of people came crawling out of the woodwork to claim that it (or fact-checking more generally) was part of some leftist agenda. That is, in my opinion, a fascinating and hilarious self-own. It is fundamentally an admission by these people on the right that the facts are not on their side.