The COVID era has been a golden age of misinformation. It has seen the development of innumerable false claims and shoddy arguments, and it has breathed new life into ancient anti-vaccine tropes. Indeed, I find it impossible to make any posts about this topic on social media without the comments immediately becoming a raging dumpster fire of falsehoods. The arguments are so innumerable that trying to debate them with someone quickly becomes an exercise in futility that feels like fighting the mighty hydra. As soon as one argument is debunked, several more pop up to take its place.

This article is my attempt to ameliorate that situation by compiling most of the common arguments I encounter into a single location where they can all be debunked in one fell swoop. Because there are so many of them, I will address each one only briefly and provide citations to the relevant studies as well as links to articles that go into more detail. To those fighting the good fight against misinformation, rock on, and I hope this article will make a useful addition to your arsenal. To those who arrived on this page because someone directed you here when you made one of these bad arguments, please actually look at the evidence. Please stop listening to your favorite politician, commentator, youtuber, fringe doctor, etc. and look at the actual evidence.

Many of these arguments are interrelated and somewhat redundant, but they are often presented as separate arguments, so I wanted to deal with each explicitly here. They are ordered roughly into the following categories:

- 1–8 = Arguments about COVID risk/mortality rates

- 9–13 = Arguments based on the novelty of the vaccines

- 14–20 = Arguments about vaccine effectiveness

- 21–23 = Arguments about the reliability of science

- 24–30 = Miscellaneous: conspiracy theories, VAERS, anecdotes, etc.

With that out of the way, let’s do this.

Bad argument #1: COVID isn’t dangerous

Reality: Yes it is; millions are dead

Over 5.5 million people have already died, including over 850,000 in the USA alone. Something that has killed millions of people in only two years is, by definition, dangerous. Indeed, COVID was the 3rd highest cause of death in the USA in 2020 (Murphy et al. 2021) and 2021 (only cancer and heart disease were higher), and during outbreaks, it spiked to the #1 slot (see graph here). So unless you are going to tell me that accidents, stroke, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and every other cause of death that COVID beat aren’t dangerous, please stop making the insane claim that COVID isn’t dangerous. Finally, death is not the only possible negative outcome, and hospitalization, long-term effects, time off work, etc. should all be considered (Mitrani et al. 2020; Fraser 2020).

Bad argument #2: 99.9% survive

Reality: That still means millions of deaths

- The survival rate varies greatly among ages, populations, strains, etc. So a blanket number like this isn’t accurate or useful.

- That is still a high death rate, and it has resulted in millions of deaths (see #1).

- Diseases can be very dangerous to a population either by having a high mortality rate or by having a high infection rate (or both), and COVID has a very high infection rate. If you have two diseases, one of which has a 10% mortality rate but only infects 100,000 people, and the other of which only has a 0.1% mortality rate but infects 10,000,000 people, you end up with 10,000 deaths either way.

More details here

Bad argument #3: People only die because of comorbidities, so the actual COVID death rate is very low/COVID death rates are inflated by comorbidities.

Reality: Comorbidities don’t change the fact that these people died as a result of COVID

Comorbidities are simply additional factors that contributed to a death, and their existence does not negate the critical role of COVID in those deaths. If someone with a blood clotting disorder is stabbed and bleeds to death, the clotting disorder will be listed as a comorbidity because it was a contributing factor, but it would be insane to argue that this death is “inflating stabbing mortality rates” or that “stabbing wasn’t really the cause of death, because they had a clotting disorder.” The fact remains that they would not have died at that point in time if it had not been for the stabbing, and something that would have prevented the stabbing would also have prevented their death. The same is true with COVID comorbidities. In most cases, these people would not have died at this particular point in time if it wasn’t for COVID. Further, a huge portion of people have conditions that predispose them to severe COVID and would count as comorbidities if they die (CDC: People with Certain Medical Conditions).

More details here.

Bad argument #4: It’s no worse than the flu

Reality: Yes it is

In the United States of America, influenza kills between 12,000 and 52,000 people annually, with a total of 342,000 flu deaths from the 2010–2020 seasons (CDC flu data). In sharp contrast, COVID has already killed >850,000 Americans, and in 2020 alone, the USA suffered 377,883 COVID deaths (Ahmad et al. 2021), with an even higher number of deaths in 2021. In other words, COVID kills more people in a single year than the flu kills in a decade. So please stop with this nonsense that it is no worse than the flu.

Bad argument #5: I’m young and healthy, so I don’t need a vaccine

Reality: You can still become seriously ill and/or spread it to others

Being young and healthy lowers your risk, but it does not eliminate it. There are thousands of previously young healthy people who have died of COVID, and thousands more who became seriously ill (see CDC data). Further, young healthy people can still spread it to those who aren’t young and healthy (see #).

Also see #25

Bad argument #6: I trust my immune system, so I don’t need vaccines

Reality: Your immune system is only as good as its training

Even a healthy immune system has to learn how to fight a novel disease before it can do so effectively. Vaccines simply train your immune system so that it knows how to fight a disease like COVID when it encounters the real thing. This argument is about like saying, “I trust the military, so I don’t think they need intelligence reports on the enemy.”

Details here

Bad argument #7: Humans have survived for thousands of years without vaccines

Reality: The species has lived, but millions of individuals have died.

Homo sapiens as a species has survived, but countless individuals died, and since their invention, vaccines have saved untold millions of lives. No one is saying that COVID is going to wipe us our as a species. Rather, we are saying that millions of individuals could be saved with the vaccines.

More details here

Bad argument #8: Maybe previous strains were dangerous, but Omicron isn’t

Reality: Omicron is less dangerous, but still dangerous

Early evidence does suggest that Omicron is less deadly than other strains, but that does not mean it isn’t dangerous. Further, the current data also suggest that it is more easily transmitted, which means that your total risk may still be high, because risk is determined by the combination of the probability of catching the disease and probability of serious injury or death if you catch the disease (see #2). Further, even a less-deadly strain can still have substantial impacts by flooding hospitals with thousands of infected patients, which is exactly what is happening. Indeed, the USA just set a new record for hospitalized COVID patients, and remember that deaths always lag behind infections and hospitalizations.

Bad argument #9: The vaccines alter your DNA

Reality: mRNA cannot alter your DNA, and this is not genetic engineering.

DNA is the master copy of your genetic material and is stored in your cells’ nuclei. Think of DNA like the original architectural plans for a building. To make proteins, that double-stranded DNA gets transcribed in single-stranded RNA, and the RNA is then transported to ribosomes which use it as the plans for making proteins. Think of RNA like the blueprints used at a worksite that have been copied from the master plans. Thus, mRNA does not alter your DNA, because that’s simply not what RNA does. Further, you get exposed to substantially more COVID mRNA during an actual COVID infection, and your body is already teaming with RNA from the millions of micro-organisms that live in and on you.

DNA is the master copy of your genetic material and is stored in your cells’ nuclei. Think of DNA like the original architectural plans for a building. To make proteins, that double-stranded DNA gets transcribed in single-stranded RNA, and the RNA is then transported to ribosomes which use it as the plans for making proteins. Think of RNA like the blueprints used at a worksite that have been copied from the master plans. Thus, mRNA does not alter your DNA, because that’s simply not what RNA does. Further, you get exposed to substantially more COVID mRNA during an actual COVID infection, and your body is already teaming with RNA from the millions of micro-organisms that live in and on you.

More details here

Bad argument #10: The vaccines are too new/rushed

Reality: No, they aren’t/weren’t

- We have been studying mRNA vaccines for many years (e.g., this study [Fleeton et al. 2001] from over two decades ago, also see this review: Pardi et al. 2018). These studies include human trials, some of which followed patients for over a year (Craenenbroeck et al. 2015, Bahl 2017, Alberer et al. 2017, Feldman et al. 2019).

- These vaccines were developed quickly by using that existing knowledge, investing heavily in the vaccines, and streamlining the process by running different stages in parallel. All normal checks and criteria for approval were still met (i.e., they weren’t rushed).

- The key to determining safety and efficiency is sample size, not time, and because COVID is so prevalent, scientists were able to generate massive sample sizes extremely quickly (Polack et al. 2020, Mahase 2020, Qianhui et al. 2021, Barda et al. 2021b just to list a few). These are some of the largest studies in medical history, and the evidence they present is so comprehensive and compelling that we are well beyond the stage of reasonable doubt. Anyone who says that we don’t know enough about these vaccines is either ignorant of the evidence or is choosing to blindly ignore it.

More details here and here

Bad argument #11: We don’t know the long-term effects

Reality: Yes, we do

No vaccine has ever caused a serious, unpredicted adverse event that only showed years down the road. That is simply not how vaccines work. Because vaccines train the immune system before being quickly eliminated, their effects happen quickly (within minutes or days, not years later). We now have way more than enough data to be highly confident in the safety of these vaccines (see #10). This concern is completely unjustified and has no scientific basis. Further, if we are going to play the game of fearing the unknown, it is far more likely that COVID itself will have long-term adverse effects than it is that the vaccines will.

More details here and here

Bad argument #12: My children and I aren’t lab rats and won’t take an experimental vaccine

Reality: The vaccines have already passed experimental testing

Again, these vaccines have been thoroughly studied using massive sample sizes (see # 10). They are no longer experimental. They have passed the experimental stage. So this argument is nonsense. It blindly ignores all of those studies.

Bad argument #13: Children and pregnant women shouldn’t be vaccinated

Reality: They are safer with vaccines

Hospitalization and death from COVID are less common in children, but they still happen, which is both tragic and preventable. The vaccines have been tested in children, and are safe and effective, resulting in 10x lower risk of hospitalization (Delahoy et al. 2021, Olson et al. 2022, Principi and Esposito 2022, Stein et al. 2022).

In contrast to children, pregnant women are actually at an increased risk of serious adverse events from COVID, but like children, the vaccines have been well-studied, and a large study (>40,000 participants) found that COVID19 vaccination is safe during pregnancy (Lipkind et al. 2022).

Bad argument #14: The vaccines aren’t 100% effective

Reality: Nothing is 100% effective, but they are still very useful

This one is an anti-vaccer classic that has been around for ages. The reality is that almost nothing is 100% effective. Helmets, parachutes, seat belts, air bags, birth control, etc. are all less than 100% effective, yet clearly the are very useful. Risk is inherently about probabilities, not absolutes. So, when we talk about how well vaccines work, we are always talking about risk reduction, not risk elimination, and the vaccines do greatly reduce risk (see #10, 15, 16).

More details here and here.

Bad argument #15: The vaccines don’t prevent you from getting COVID (breakthrough cases)

Reality: They reduce risk and severity

Again, almost nothing is 100% effective (see #14), but the vaccines reduce your risk. This has been borne out by study (Polack et al. 2020) after study (Mahase 2020) after study (Fowlkes et al. 2021) after study (Martínez-Baz et al. 2021). Further, even if you become infected, the vaccines dramatically reduce your risk of getting a serious infection, and the rates of hospitalizations and deaths are substantially lower among the vaccinated than among the unvaccinated (Martínez-Baz et al. 2021, Self et al. 2021, Tenforde et al. 2021). Indeed, the CDC data (COVID tracker) for October (the most recent complete month at the time I’m writing this; see update below) showed that, compared to vaccinated individuals, unvaccinated individuals were 5 times more likely to test positive for COVID and 14 times more likely to die from COVID (also see Yek et al. 2022)!

This argument is like saying, “car safety features like ABS brakes, seat belts, and air bags don’t prevent you from getting into a car accident.” Sure, they don’t completely prevent it, but some of them (e.g., brakes), make it less likely, and even if you are in an accident, they greatly reduce the risk that you will be seriously injured by the accident.

If you’ve ever had to do a risk assessment for a job, you know that risk involves both the likelihood of an event and severity if the event occurs.

Update 30-1-2022: The updated CDC data (going through December 25 2021) show that the unvaccinated are 13X more likely to test positive for COVID and 68X more likely to die from COVID, compared to people with three doses of the vaccine.

Bad argument #16: The vaccines don’t prevent you from spreading (transmitting) COVID

Reality: They reduce risk of transmission

Vaccinated individuals can spread the virus, but you have to be infected with COVID before you can spread COVID, and the vaccines greatly reduce your risk of becoming infected (see #15). Further, multiple studies (some of them quite large) have compared the COVID infection rates among family members of people who did or did not receive the vaccine, and exactly as you’d expect from herd immunity, infection rates were lower for the people with a vaccinated family member (Anoop et al. 2021, Geir et al. 2021a, Geir et al. 2021b, Singanayagam et al. 2021). So yes, breakthrough cases do happen (see #15) because nothing is 100% effective (see#14), but again, the risk is greatly reduced by the vaccines, and the data are unequivocal: vaccinating protects those around you.

Bad argument #17: Most people who catch COVID are vaccinated

Reality: You have to look at ratios, not raw numbers

This claim is often untrue, but even when it is true, that is only because most people are vaccinated. We have to look at the rates not the raw numbers. By way of analogy, most car accidents involve sober drivers, but that doesn’t mean it is safer to drive drunk; it’s simply that most people drive sober, and we can see this when we look at the rates. Even so, when it comes to vaccines, the rates (infections per person) clearly show that the vaccines work and reduce risk (Polack et al. 2020, Mahase 2020, Fowlkes et al. 2021, Martínez-Baz et al. 2021, see #10 and 15).

More details here and here

Bad argument #18: The vaccines are less effective against Omicron

Reality: They still help, and boosters largely restore effectiveness

Omicron is still too new for us to have a completely clear picture of this. Current evidence does suggest that the vaccines are less effective against omicron than they were against delta (particularly when it comes to completely preventing asymptomatic infection, but see #20 regarding boosters), but they current evidence also suggests that they still greatly reduce your risk of getting a serious infection that would require hospitalization. Indeed, a report that was just released by the UK Health Security Agency (2021) found that 3 doses of the vaccine were 88% effective at preventing hospitalization from omicron. Similarly, data from South Africa showed that even just two doses of the Pfizer vaccine resulted in 70% effectiveness at preventing hospitalization from omicron (Collie et al. 2021).

See #20 on boosters

Bad argument #19: If vaccines work, why do you care if I am vaccinated?

Reality: Because I care about others

- Vaccines greatly reduce risk, but they aren’t 100% effective (see #14–16).

- Many people can’t be vaccinated due to medical issues, but when everyone else is vaccinated, they are protected by herd immunity.

- Outbreaks can overwhelm the medical system and prevent others from getting the treatments they need (multiple uninfected people have died because of this; Sabbatini, et al. 2021).

- When most people are vaccinated, the risk of new strains emerging is reduced because it is harder for the virus to replicate (which is where new mutations come from) and spread.

- Outbreaks hurt everyone by harming the economy, causing lockdowns and restrictions, interfering with travel, etc.

Bad argument #20: They said we’d only need two doses, but now it’s three

Reality: So what? Why is that a problem?

- Many routine vaccines require boosters, and we’ve always known that was a possibility with COVID.

- Boosters really aren’t a big deal (they are safe [Hause et al. 2021]), and they greatly increase vaccine effectiveness (e.g., Barda et al. 2021a which had a sample size of over 1 million).

- The primary reason they are being pushed so hard now is because the situation has changed (i.e., a new variant [omicron] emerged, which is something scientists have warned about all along). Data are still limited and being reviewed, but early results suggests that the effectiveness of 2 doses is greatly reduced, but a 3rd dose (booster) helps to restore effectiveness (Gardner and Kilpatrick 2021*, Garcia-Beltran et al. 2022, Muik et al. 2022 [* this is a preprint and has not been peer-reviewed]).

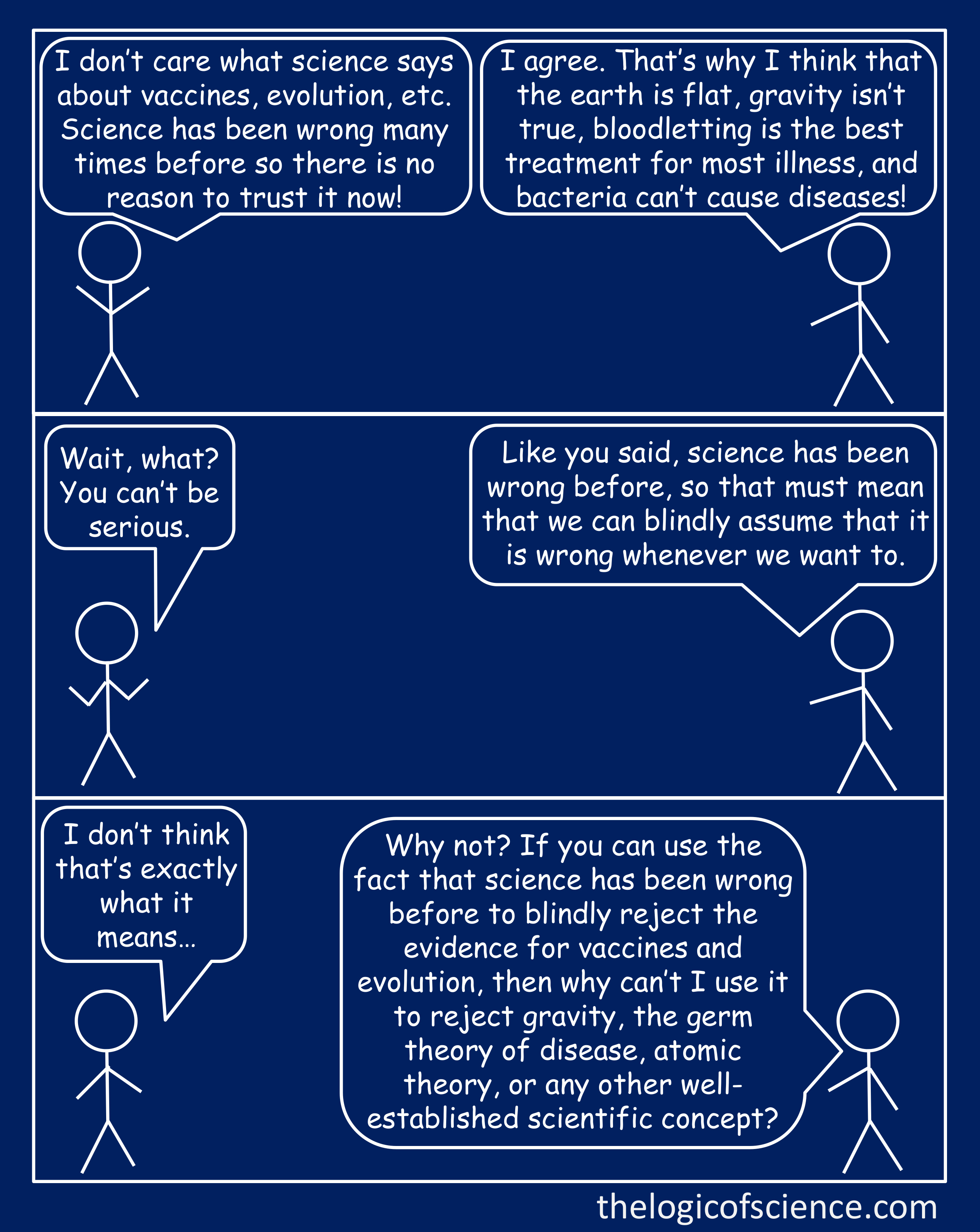

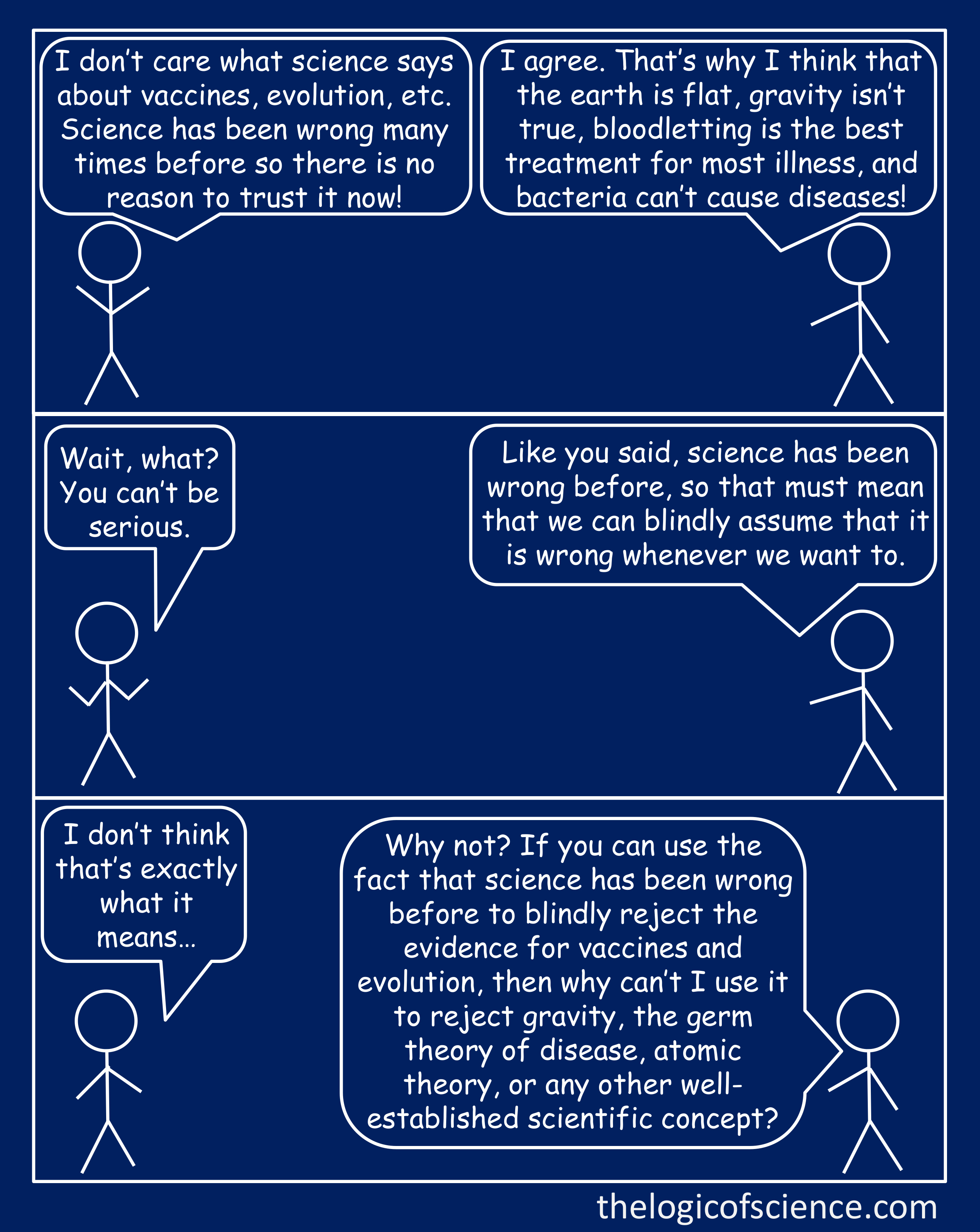

Bad argument #21: But science has been wrong before

Bad argument #21: But science has been wrong before

Reality: This is a misunderstanding of how science works

Science is inherently the process of discrediting previous ideas, but in the modern era, previous ideas generally turn out to be incomplete more than entirely wrong, particularly for topics like vaccines where the evidence for their safety and effectiveness of vaccinees is overwhelming (see #10, 13–16). Further, the fact that scientific conclusions have been wrong before absolutely does not mean that you can blindly assume that the current evidence is wrong. If it did, you could reject any scientific result you like on the basis that science has been wrong before. You have to present actual evidence that the current conclusions are wrong, and there is simply no evidence that we are wrong about these vaccines.

Details here and here.

Also, see posts here, here, and here regarding the nature of a scientific consensus.

See this post regarding the claim that most scientific studies are wrong.

Bad argument #22: They laughed at Galileo and Columbus

Reality: This is a misconception and doesn’t mean you’re right

Galileo was mostly criticized by the church (i.e., people who were ignoring evidence because of ideology) not his fellow scientists. Also, critically, he had actual evidence, not conjecture, conspiracy theories, or a blind denial of evidence. Columbus, on the other hand was painfully wrong about the size of the earth (everyone already knew it was round) and just got lucky that there was another continent that Europeans didn’t know about. Finally, again, you must have actual evidence that current conclusions are wrong (see #21).

Details here and here and here.

Bad argument #23: There used to be a consensus that smoking was safe

Reality: No there wasn’t

This is a complete myth. Scientists have known since WWII that smoking was dangerous (Proctor 2012). Tobacco companies never managed to buy off more than a handful of doctors and scientists. What they had was a good PR team, not a scientific consensus (also see #21 and 22).

See posts here, here, and here regarding the nature of a scientific consensus.

See this post regarding the claim that most scientific studies are wrong.

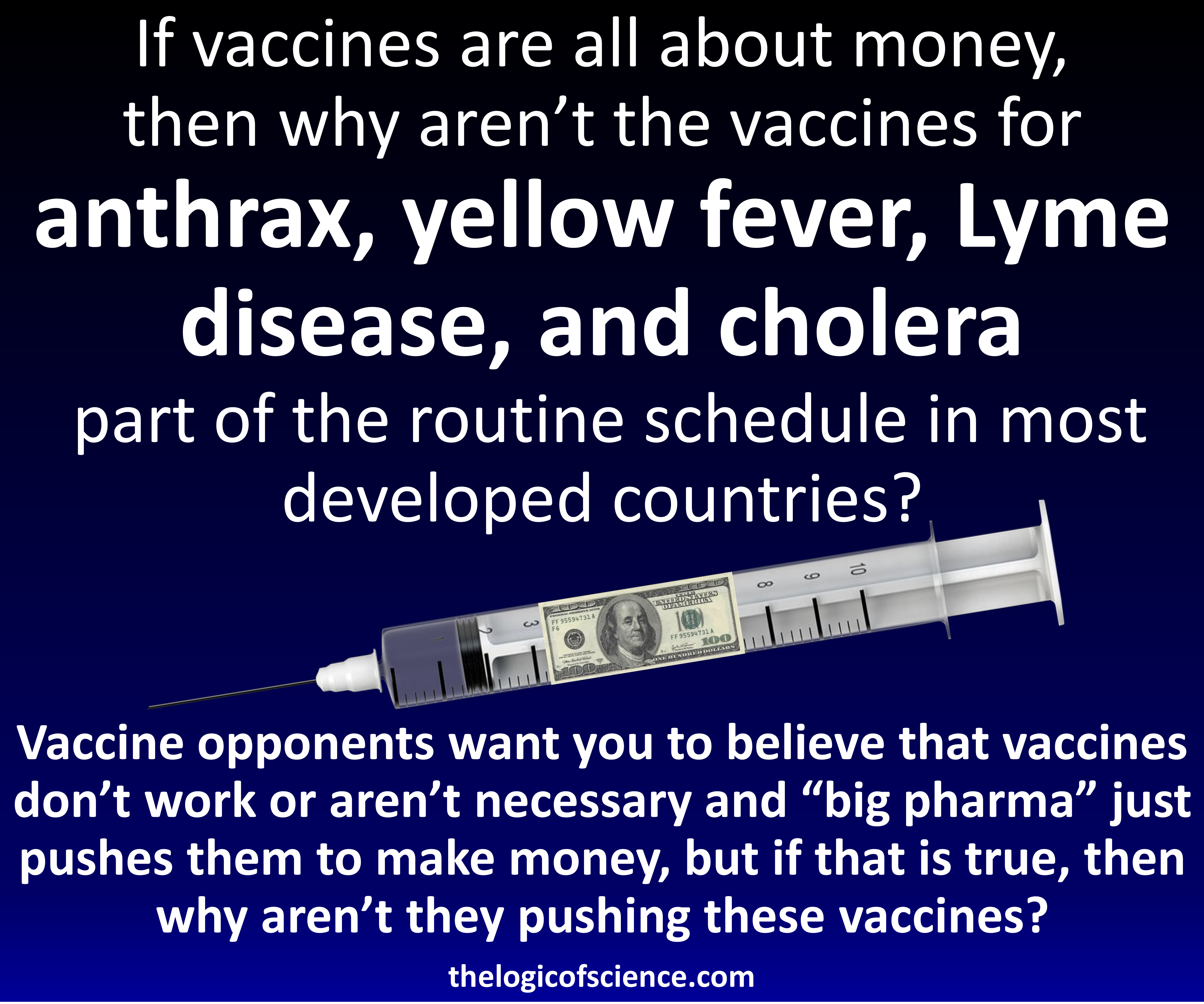

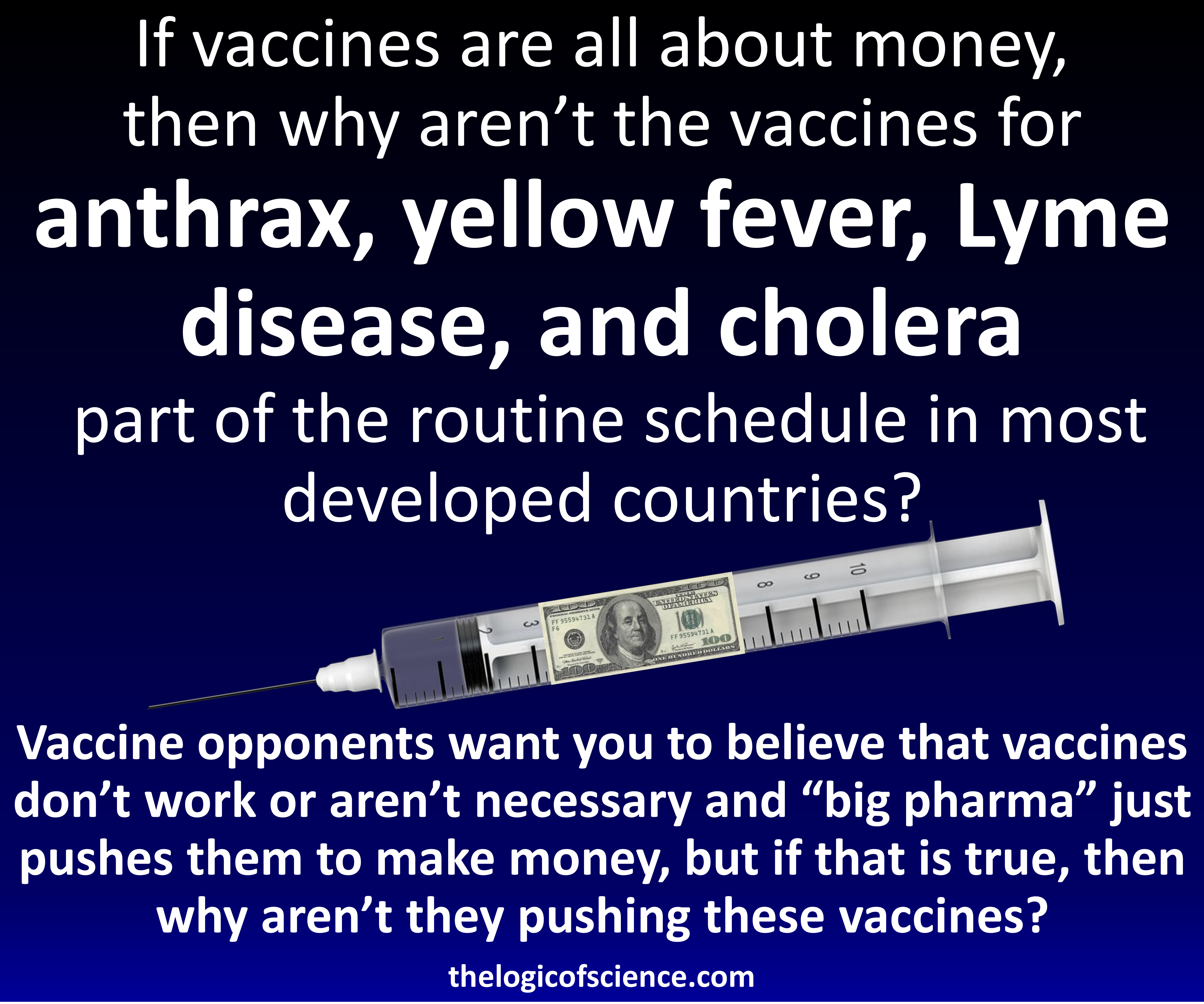

Bad argument #24: I just don’t trust pharmaceutical companies/It’s all about money

Bad argument #24: I just don’t trust pharmaceutical companies/It’s all about money

Reality: It’s about trusting science, not “big pharma”

I don’t trust “big pharma” either, and I’m all for tight regulations and oversight, removing lobbyist, making drugs affordable, etc. I do, however, trust the science, a very large portion of which has been conducted by independent scientists who are not funded by pharmaceutical companies. The thing about science is that it is self-correcting. If pharmaceutical companies faked their data, other scientists would find out and report it. Keep in mind also that there are multiple competing pharmaceutical companies who would love to discredit each other

See posts here and here for more on the “follow the money” argument.

Bad argument #25: [insert personal anecdotes]

Reality: Anecdotes are pretty meaningless in science

The fact that event A happened before event B does not indicate (or even suggest) that event A caused event B (that’s known as a post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy). At best, anecdotes can suggest things to be studied, but to actually determine causation, safety, or efficacy we need large properly controlled studies, and those have shown that these vaccines are safe and effective (see #10, 13–16). Anecdotes simply are not reliable evidence of causation.

Additionally, one specific anecdote I’d like to deal with is the argument that, “I got COVID and was fine; therefore, it’s not dangerous.” This is known as a survivorship bias: i.e., those who died are inherently not here to share their stories. The fact that you were fine does not alter the fact that millions weren’t. Similarly, if you are unvaccinated, before you go around boasting that you have an incredible immune system because you haven’t caught COVID, consider the fact that every single person who has caught COVID could have bragged about not catching COVID until the moment they caught it. In other words, contemplate the possibility that you simply haven’t caught it yet.

More details here and here and here.

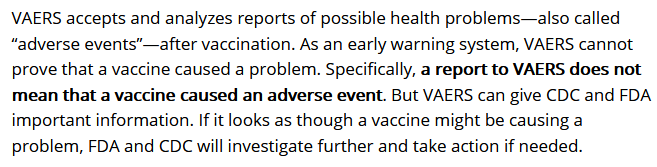

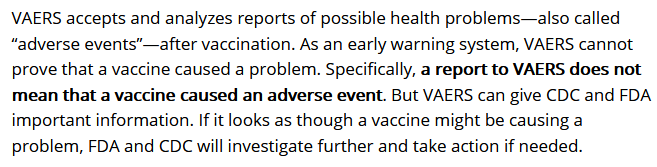

Bad argument #26: There are tens of thousands of vaccine injuries and deaths on VAERS

Reality: Being reported in VAERS does not mean that the vaccine caused the problem

VAERS is a self-reported database that often contains all manner of absurdities. It is meant as an early warning system, and you have to be very, very careful when using it. The fact that something was reported in VAERS absolutely does not mean that the vaccine caused it. VAERS itself is explicit about that (see screenshot below [bold was in the original]; also see #25).

More details here

Bad argument #27: But there are real risks from the vaccines

Reality: Yes, but they are rare, and the benefits outweigh the risks

Adverse events exist for all real medications. For vaccines, however, serious side effects are very rare, and the benefits from the vaccines far outweigh the risks from the disease. Risk assessment is an exercise in probabilities, and for almost any medicine, there will be some small subset who end up worse off because of it, but that doesn’t change the fact that your risk (i.e., your probability of injury) is lower with the vaccines than without them. As a result, vaccines save millions of lives, with COVID vaccines already having saved hundreds of thousands of lives (Mesle et al. 2021).

See studies cited in #10, 13–16

Bad argument #28: Various conspiracy theories/FDA corruption

Bad argument #28: Various conspiracy theories/FDA corruption

Reality: Science is about evidence, not conjecture and conspiracy theories

Conspiracy theories are endless, but they all suffer the same fundamental problems of not having any credible evidence and stating assumptions as if they are facts. No actual evidence has been presented to show that data were faked, FDA officials were bought off to push the vaccines, etc. Further, this argument ignores the facts that there are countries other than the USA and health/regulatory agencies from around the world are in widespread agreement about the safety and effectiveness of these vaccines. The research is being conducted by tens of thousands of researchers from hundreds of universities, companies, and agencies from around the world. Faking these data would require a truly insane conspiracy in which virtually all of the world’s scientists, health agencies, governments, and major pharmaceutical companies agreed to work together to lie and endanger the public. If that level of agreement among rival nations and countries sounds absurd, that’s because it is absurd.

Bad argument #29: It’s my choice/freedom. We shouldn’t have vaccine mandates

Reality: You don’t have the right to endanger others or ignore public health

This is a political argument, not a scientific argument, but I will briefly make three points. First, a large portion of the people I see making this argument also use the other arguments in this post, suggesting that they are letting political views override facts. Second, personal freedoms always end as soon as they endanger someone else, and refusing to vaccinate does endanger others (see #16, 19). This is why you have the freedom to drive a car, but not the freedom to drive recklessly or while drunk. Third, at least in most countries, the mandates simply place restrictions on the unvaccinated (e.g., requiring vaccination for a workplace), which is not the same thing as “forcing” someone (e.g., the government doesn’t “force” you to be sober, it simply restricts your right to drive unless you are sober; even so, you aren’t being “forced” to vaccinate, your ability to work certain jobs is simply being restricted to protect your coworkers).

Bad argument #:30 But I heard on Youtube, Facebook, Joe Rogan, Fox, OAN, some random guy with cool sunglasses sitting in a pickup truck, etc…

Reality: Those are not good sources

Please just stop. Stop with the deluded belief that you know more than the experts. Stop listening to unqualified people. Stop cherry-picking your experts. Multiple massive studies have clearly showed that COVID is dangerous and the vaccines are safe, effective, and help protect you and those around you. Either you accept that evidence or you deny it.

More on fact checking

Related posts

Literature cited

- Ahmad et al. 2021. Provisional Mortality Data — United States, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 70:519–522

- Alberer et al. 2017. Safety and immunogenicity of a mRNA rabies vaccine in healthy adults: an open-label, non-randomised, prospective, first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial. Lancet 390:1511–1520.

- Anoop et al. 2021. Effect of Vaccination on Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med 385:1718-1720

- Bahl 2017. Preclinical and Clinical Demonstration of Immunogenicity by mRNA Vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 Influenza Viruses. Molecular Therapy 25:1316–1327.

- Barda et al. 2021a. Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: an observational study. Lancet 398: 2093-2100

- Barda et al. 2021b. Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Setting. The New England Journal of Medicine

- Collie et al. 2021. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 vaccine against Omicron variant in South Africa. New England Journal of Medicine

- COVID tracker. CDC: Rates of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by Vaccination Status. Accessed 01-01-2022.

- Craenenbroeck et al. 2015. Induction of cytomegalovirus-specific T cell responses in healthy volunteers and allogeneic stem cell recipients using vaccination with messenger RNA-transfected dendritic cells. Transplantation 99:120–127.

- Delahoy et al. 2021. Hospitalizations Associated with COVID-19 Among Children and Adolescents — COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1, 2020–August 14, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 70:1255–1260

- Feldman et al. 2019. mRNA vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 influenza viruses of pandemic potential are immunogenic and well tolerated in healthy adults in phase 1 randomized clinical trials. Vaccine 37:3326–3334.

- Fleeton 2001. Self-replicative RNA vaccines elicit protection against influenza A virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and a tickborne encephalitis virus. Journal of Infectious Diseases 183:1395–1398.

- Fowlkes et al. 2021. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines in Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Frontline Workers Before and During B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant Predominance — Eight U.S. Locations, December 2020–August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 70: 1167–1169.

- Fraser 2020. Long term respiratory complications of covid-19. BMJ 370.

- Garcia-Beltran et al. 2022. mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell

- Gardner and Kilpatrick 2021. Estimates of reduced vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization, infection transmission and symptomatic disease of a new SARS-CoV-2 variant, Omicron2 (B.1.1.529), using neutralizing antibody titers. (preprint).

- Geir et al. 2021a. Vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 transmission to household contacts during dominance of Delta variant (B.1.617.2), the Netherlands, August to September 2021. Euro Surveill 26:2100977

- Geir et al. 2021b. Vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 transmission and infections among household and other close contacts of confirmed cases, the Netherlands, February to May 2021. Euro Surveill 26:2100640

- Hause et al. 2021. Safety monitoring of an additional dose of COVID-19 vaccine — United States, August 12–September 19, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 70: 1379–1384.

- Lipkind et al. 2022. Receipt of COVID-19 Vaccine During Pregnancy and Preterm or Small-for-Gestational-Age at Birth — Eight Integrated Health Care Organizations, United States, December 15, 2020–July 22, 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 71:26–30

- Mahase 2020. Covid-19: Moderna vaccine is nearly 95% effective, trial involving high risk and elderly people shows. BMJ 371.

- Martínez-Baz et al. 2021. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing

- SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalisation, Navarre, Spain, January to April 2021. Euro Surveill. 26:2100438

- Mesle et al. 2021. Estimated number of deaths directly averted in people 60 years and older as a result of COVID-19 vaccination in the WHO European Region, December 2020 to November 2021. 26

- Mitrani et al. 2020. COVID19 cardiac injury: Implications for long-term surveillance and outcomes in survivors. Heart Rhythm 17:1984–1990.

- Muik et al. 2022. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron by BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine–elicited human sera. Science

- Murphy et al. 2021. Mortality in the United States, 2020. CDC: NCHS Data Brief No. 427, December 2021

- Olson et al. 2022. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 Vaccine against Critical Covid-19 in Adolescents. New England Journal of Medicine

- Pardi et al. 2018. mRNA vaccines — a new era in vaccinology. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 17:261–279

- Polack et al. 2020. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 383:2603–2615.

- Principi and Esposito 2022. Reasons in favour of universal vaccination campaign against COVID-19 in the pediatric population. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 48

- Proctor 2012. The history of the discovery of the cigarette-lung cancer link: evidentiary traditions, corporate denial, global toll. Tobacco Control 21: 87-91

- Qianhui et al. 2021. Evaluation of the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid review. BMC Medicine 19:173.

- Sabbatini, et al. 2021. Excess mortality among patients hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Hospital Medicine

- Self et al. 2021. Comparative effectiveness of Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, and Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) vaccines in preventing COVID-19 hospitalizations among adults without immunocompromising conditions — United States, March–August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 70:1337–1343

- Stein et al. 2022. The Burden of COVID-19 in Children and Its Prevention by Vaccination: A Joint Statement of the Israeli Pediatric Association and the Israeli Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Vaccines 10.

- Singanayagam et al. 2021. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 29:00648-4

- Tenforde et al. 2021. Effectiveness of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 messenger RNA vaccines for preventing coronavirus disease 2019 hospitalizations in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases

- UK Health Security Agency. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England. Technical briefing: Update on hospitalisation and vaccine effectiveness for Omicron VOC-21NOV-01 (B.1.1.529).

- Yek et al. 2022. Risk Factors for Severe COVID-19 Outcomes Among Persons Aged ≥18 Years Who Completed a Primary COVID-19 Vaccination Series — 465 Health Care Facilities, United States, December 2020–October 2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 71:19-25

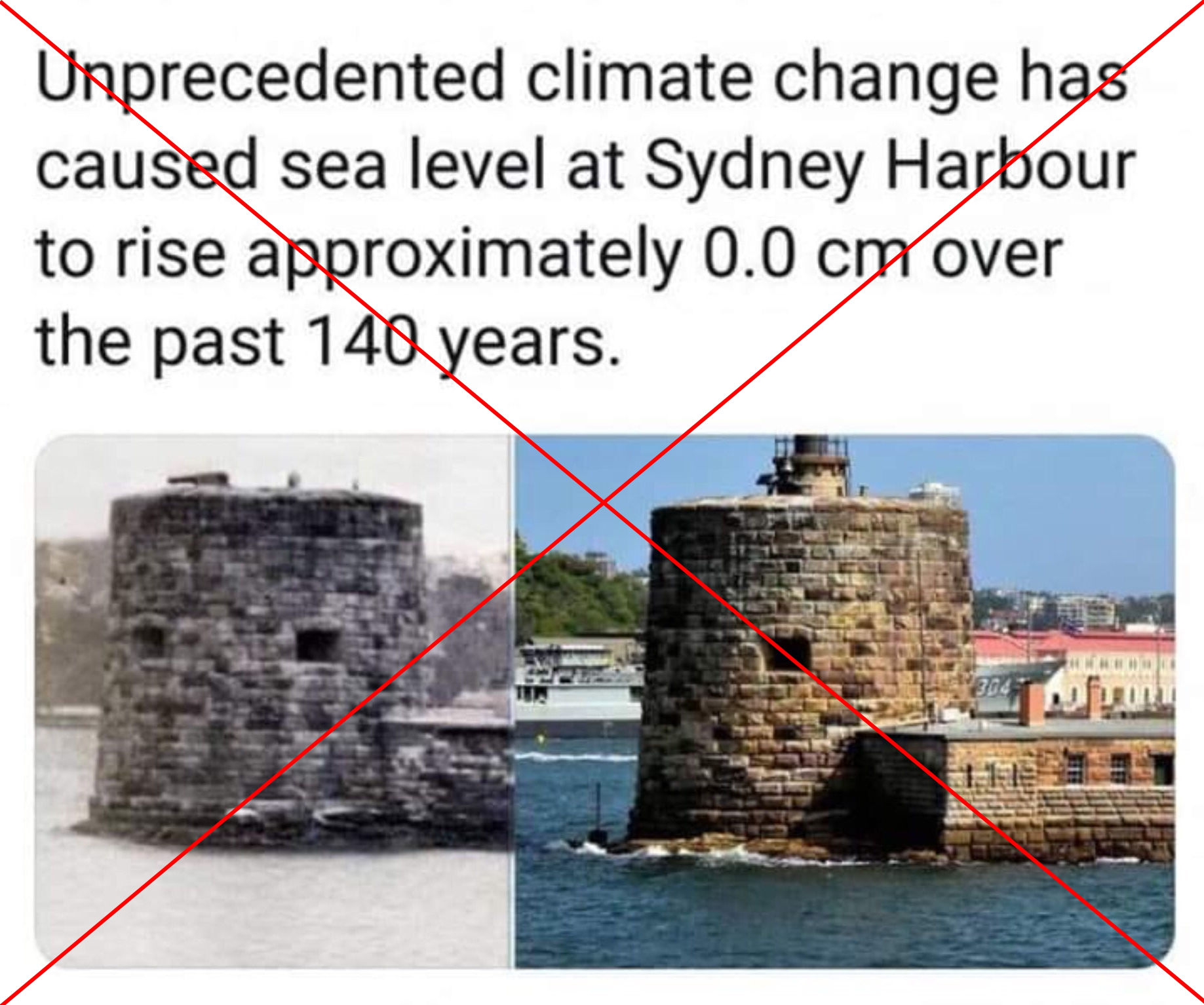

Yesterday, I posted the fairly innocuous image above on the TLoS Facebook page, and the results were both fascinating and horrifying. Numerous people took time out of their day to embarrass themselves by doubling down and attacking fact-checkers, often with truly deranged comments that were totally detached from reality and clearly illustrated why fact checking is so important. Further, multiple people (all on one side of the political aisle) incorrectly interpreted this as a political post, a response which is delightfully revealing. Given the responses that this post engendered, I think it will be instructive to clarify several points and discuss some of the comments. This is hardly the first time that I have written about fact-checking, and you can read a much longer post on it here.

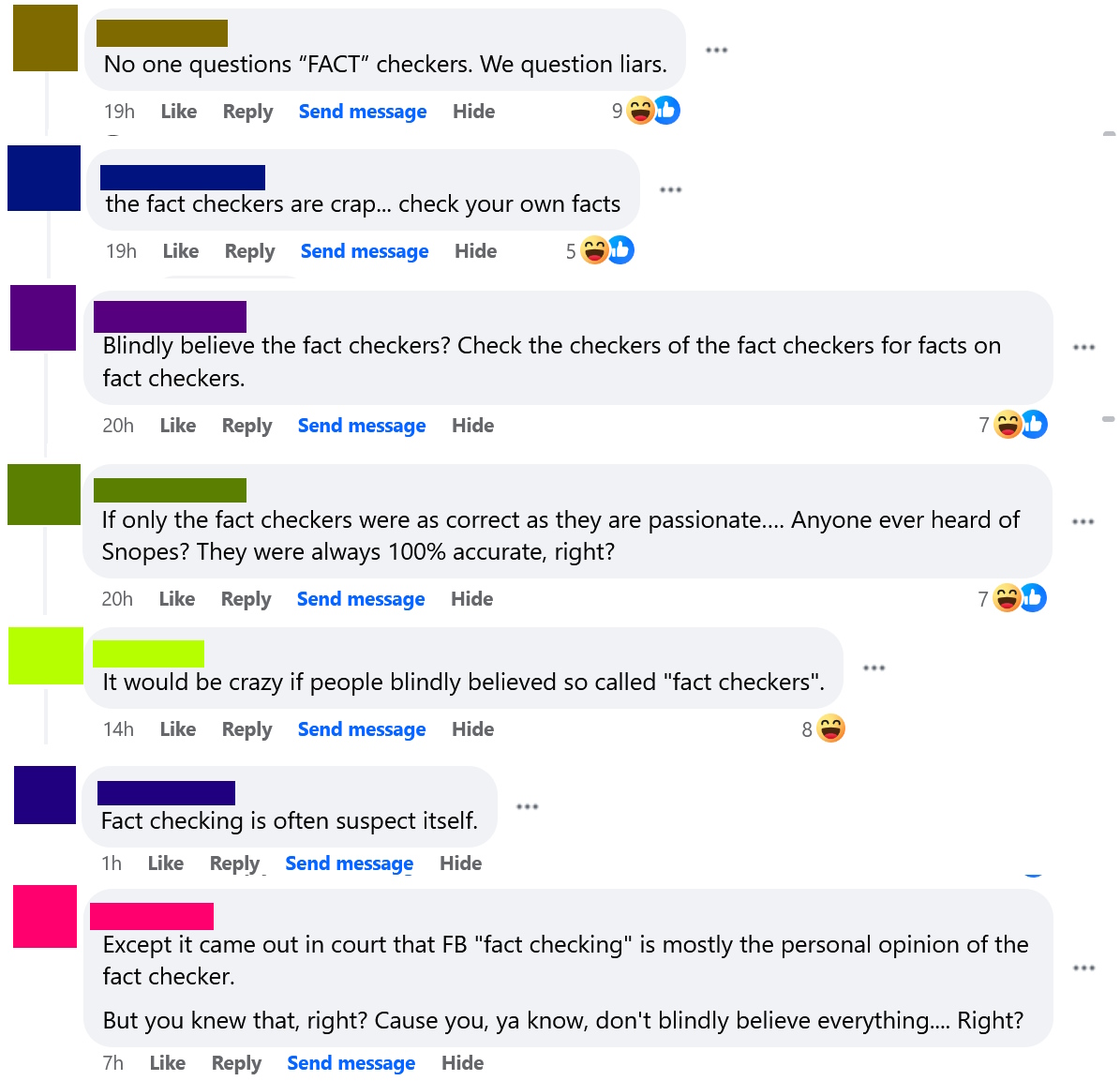

Yesterday, I posted the fairly innocuous image above on the TLoS Facebook page, and the results were both fascinating and horrifying. Numerous people took time out of their day to embarrass themselves by doubling down and attacking fact-checkers, often with truly deranged comments that were totally detached from reality and clearly illustrated why fact checking is so important. Further, multiple people (all on one side of the political aisle) incorrectly interpreted this as a political post, a response which is delightfully revealing. Given the responses that this post engendered, I think it will be instructive to clarify several points and discuss some of the comments. This is hardly the first time that I have written about fact-checking, and you can read a much longer post on it here. First, I want to deal with the strawman that I was suggesting that people should blindly believe fact-checkers (see a selection of such comments to the right). I have never said anything of the sort, and, in fact, the original post wasn’t about professional fact-checkers at all. Rather it was about individuals checking facts before believing something.

First, I want to deal with the strawman that I was suggesting that people should blindly believe fact-checkers (see a selection of such comments to the right). I have never said anything of the sort, and, in fact, the original post wasn’t about professional fact-checkers at all. Rather it was about individuals checking facts before believing something. Let’s look at one case that I found particularly amusing. After a general statement against Snopes, the person in red doubled down with the claim that Snopes had testified before Congress that their fact checks were actually opinions (note that they did not specify Snopes, but that was the subject being discussed, and the “the” appears to be a typo for “they”). This would have been a great place for red to fact-check before posting, because Google failed to reveal any such testimony, and when pressed for evidence that such a confession had taken place, red posted a NY Post article about Facebook (not Snopes) testifying in a trail (not before Congress), and the NY Post article took things wildly out of context (as it often does). When this was pointed out to red, rather than admitting his mistakes, he doubled down and accused everyone else of being the blind, biased ones.

Let’s look at one case that I found particularly amusing. After a general statement against Snopes, the person in red doubled down with the claim that Snopes had testified before Congress that their fact checks were actually opinions (note that they did not specify Snopes, but that was the subject being discussed, and the “the” appears to be a typo for “they”). This would have been a great place for red to fact-check before posting, because Google failed to reveal any such testimony, and when pressed for evidence that such a confession had taken place, red posted a NY Post article about Facebook (not Snopes) testifying in a trail (not before Congress), and the NY Post article took things wildly out of context (as it often does). When this was pointed out to red, rather than admitting his mistakes, he doubled down and accused everyone else of being the blind, biased ones. Finally, let’s briefly turn to politics for a second, because when I made my initial post something fascinating happened. The post was not even remotely political. Nevertheless, a bunch of people came crawling out of the woodwork to claim that it (or fact-checking more generally) was part of some leftist agenda. That is, in my opinion, a fascinating and hilarious self-own. It is fundamentally an admission by these people on the right that the facts are not on their side.

Finally, let’s briefly turn to politics for a second, because when I made my initial post something fascinating happened. The post was not even remotely political. Nevertheless, a bunch of people came crawling out of the woodwork to claim that it (or fact-checking more generally) was part of some leftist agenda. That is, in my opinion, a fascinating and hilarious self-own. It is fundamentally an admission by these people on the right that the facts are not on their side.

DNA is the master copy of your genetic material and is stored in your cells’ nuclei. Think of DNA like the original architectural plans for a building. To make proteins, that double-stranded DNA gets transcribed in single-stranded RNA, and the RNA is then transported to ribosomes which use it as the plans for making proteins. Think of RNA like the blueprints used at a worksite that have been copied from the master plans. Thus, mRNA does not alter your DNA, because that’s simply not what RNA does. Further, you get exposed to substantially more COVID mRNA during an actual COVID infection, and your body is already teaming with RNA from the millions of micro-organisms that live in and on you.

DNA is the master copy of your genetic material and is stored in your cells’ nuclei. Think of DNA like the original architectural plans for a building. To make proteins, that double-stranded DNA gets transcribed in single-stranded RNA, and the RNA is then transported to ribosomes which use it as the plans for making proteins. Think of RNA like the blueprints used at a worksite that have been copied from the master plans. Thus, mRNA does not alter your DNA, because that’s simply not what RNA does. Further, you get exposed to substantially more COVID mRNA during an actual COVID infection, and your body is already teaming with RNA from the millions of micro-organisms that live in and on you.

Bad argument #21: But science has been wrong before

Bad argument #21: But science has been wrong before Bad argument #24: I just don’t trust pharmaceutical companies/It’s all about money

Bad argument #24: I just don’t trust pharmaceutical companies/It’s all about money

Bad argument #28: Various conspiracy theories/FDA corruption

Bad argument #28: Various conspiracy theories/FDA corruption