“Science used to say that smoking was safe, so why should we ‘trust the science’ when it says that vaccines are safe and effective, climate change is real, or GMOs are safe?”

This is one of the most common excuses I hear for rejecting modern scientific evidence. People throw this argument around like a “get out of jail free” card for blindly dismissing any studies they don’t like. The argument is, however, fundamentally flawed in every way. It suffers all the usual problems with “science has been wrong before” arguments, and its core claim is simply false. There was never a scientific consensus that smoking was safe, and the true history of the science of tobacco actually reveals just how important it is to “trust the science” and why anecdotes, appeals to antiquity, and appeals to nature don’t work.

Note: This post pulled heavily from Doll’s (1998) review of the history of tobacco, and I highly recommend reading that paper in full.

Traditional tobacco use

Smoking tobacco is an ancient practice. Archeological evidence shows that people have used tobacco for at least 2500 years. It was used by the Mayans for religious ceremonies, medicine, and recreation, and those uses spread throughout the Americas. This is important to realize because there are many today who argue that natural remedies must be safe and effective by simple virtue of the fact that they are “natural” (this is the “appeal to nature fallacy”). Tobacco is, however, completely natural, yet it is very harmful to human health. So, if appeals to nature were reliable, then smoking should be safe.

Similarly, the supposed medical benefits of smoking tobacco were supported by countless anecdotes. Generation after generation saw examples of people getting better after smoking tobacco, so surely it must work, right? Wrong! Anecdotes are not evidence of causation, and coincidences and placebo effects do happen (saying “I took X then got better, therefore X works” is a post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy)

Likewise, I frequently encounter people who criticize “western” medicine and insist that indigenous peoples have “other ways of knowing” that are superior to science. Here again, if that was true, and we should rely on traditional knowledge instead of modern science, then we’d have to conclude that smoking is not only safe, but actually medically beneficial!

Don’t get me wrong, indigenous peoples often do have a wealth of knowledge about the environment, and their knowledge provides excellent starting points for scientific research. I am all for scientists collaborating with indigenous groups and working with them. Those relationships can be extremely valuable, but at the end of the day, anything about the physical world that is actually true has to be able to pass scientific testing. The fact that something has been used for hundreds or thousands of years simply is not sufficient.

This understanding is important for things like acupuncture, cupping, and a host of other “alternative medicines.” I constantly hear people say things like, “well acupuncture has been used for thousands of years, so surely it must work. Why else would they have used it for so long?” The history of smoking clearly shows why that thinking doesn’t work. The fact that something has been used for a long time does not in any way shape or form indicate that it works (this is known as an appeal to tradition fallacy).

In short, we developed science precisely because anecdotes, appeals to nature, and appeals to antiquity don’t work. Science is, hands down, the most reliable tool we have ever invented for understanding the natural world.

Scientific history

When Europeans arrived in the Americas, they quickly adopted tobacco use and brought it back to Europe with them, where it was once again used for pleasure as well as being used to treat a range of conditions including asthma, coughing, cramps, parasites, tumors, and various other conditions. Here again, it enjoyed a long period of use and countless anecdotes.

By the early 1900s, people had largely (although not entirely) abandoned the idea that it was medicinal, but its recreational popularity was still in full swing. There was some pushback, but those efforts weren’t based on any sound science. Indeed, over the next 50 years, little serious work was conducted on tobacco use. There were various small studies that suggested possible harm, but no truly compelling evidence emerged, and most (if not all) of those studies would not have passed modern peer review. Remember, medical science was still in its infancy, and many of the tools and experimental standards we rely on today had not been invented or established yet (this is another important point that the “science has been wrong before” crowd often ignore).

In 1950, things changed with the publication of five moderate-sized case-control studies that all showed that smoking was associated with cancer (Schrek et al. 1950; Levin et al. 1950; Mills and Porter 1950; Wynder and Graham 1950; Doll and Hill 1950). Importantly, however, case-control studies are only suggestive and cannot establish causation. Thus, their publication indicated that a potential link between smoking and cancer needed to be studied more closely, but they could not actually demonstrate that smoking was the cause of cancer.

Other studies quickly followed, including two large, prospective cohort studies (Doll and Hill 1954; Hammond and Horn 1954) which also showed that smoking was strongly associated with cancer. Cohort studies are more powerful than case-control studies and can strongly suggest causation, though they are not as conclusive as randomized controlled trials. These results caused serious debate among scientists (as is good and healthy in science), and not everyone was immediately convinced, but studies kept pouring in, including research demonstrating that tobacco causes cancer in rats and isolation of known carcinogens in tobacco smoke.

Taken together, all of these studies soon built a compelling case, and by the end of the 1950s, health agencies around the world were acknowledging that smoking causes cancer. This is a beautiful demonstration of how science should work: initial evidence suggested harm was present, and scientists, being a skeptical bunch, wanted more conclusive evidence before reaching a verdict. So more, larger, high-quality studies were done until a consensus of evidence was reached, at which point, a consensus of experts emerged and health agencies updated their conclusions and recommendations.

Critically, at no point was there compelling evidence that smoking was safe, nor was there ever a consensus of experts that it was safe. There was a long period where it was unstudied, during which many doctors smoked (as did the majority of people), but there was never a large body of evidence showing that smoking was safe, and there is a world of difference between saying, “many scientists and doctors use an untested product” and “this product has been extensively tested and scientists and doctors agree that, based on that evidence, it is safe and effective.” See the difference?

So, if you are arguing that we should not trust scientific conclusions today because science once concluded that smoking was safe, then you are wrong both logically and historically. Even before the 1950s, what little scientific evidence we had mostly suggested that smoking was dangerous, and once proper evidence emerged, scientists adopted it pretty quickly. Also, remember again that, in contrast, non-scientific approaches (other “ways of knowing”) brought us thousands of years of thinking smoking was not only safe, but beneficial.

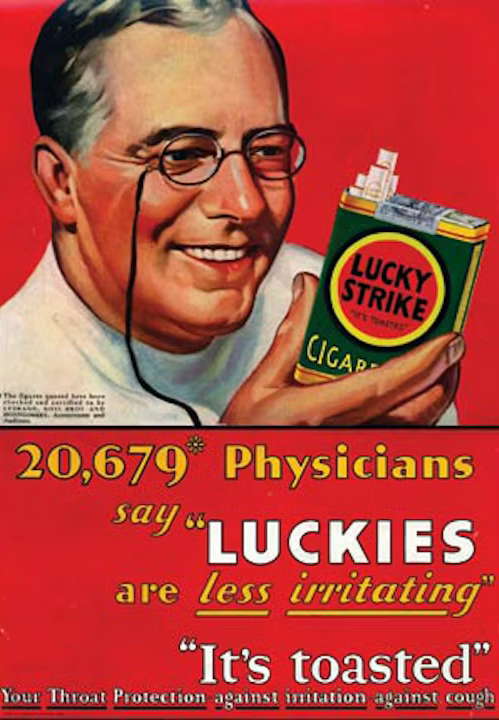

“But what about those ads with doctors smoking?”

I don’t know how to tell you this, but companies lie and mislead.

I don’t know how to tell you this, but companies lie and mislead.

Tobacco companies never actually had a consensus of experts, and they certainly didn’t have a consensus of evidence. They did, however, have a very good advertising campaign and invested a great deal of money in trying to mislead the public.

Admittedly, they did also attempt to corrupt the science. This included paying prominent scientists to testify on their behalf, funding studies showing smoking was safe, and targeting doctors at conferences and their practices. So, they did have some scientists and doctors supporting them, especially prior to the 50s when the evidence was far from conclusive. However, the studies that they funded were dwarfed by the much larger, more robust studies discussed earlier, and they were never able to purchase a consensus (see Jackler and Samji [2012] for more details about companies’ attempts to pollute the scientific literature and deceive the public).

Critically, while their campaign was very successful among the general public, and they did make a bit of a mess in the literature, they were completely unable to stop the large studies described earlier from coming out. They never managed to buy or influence a majority of scientists, they never had more than a few shoddy studies, and they were unable to suppress the truth. Once large, high-quality studies started coming out, their influence on science essentially disappeared (though they kept trying).

So given that tobacco companies where ultimately unable to block scientific progress, how does that compare with the modern science on topics like vaccines or GMOs? Several things have changed that actually make it even harder for companies to buy a consensus today.

For one thing, all modern journals require authors to declare their sources of funding and any potential conflicts of interest (including not just research funding for the current work, but also past research funding, fees for speaking engagements, etc.). Lying about conflicts of interest is a serious offense in modern science that could easily cost a researcher their career, and universities keep track of all their scientists’ funding, so an audit could easily catch the lies. None of this was true decades ago, and tobacco company-sponsored research generally did not declare who was funding it or how the researchers might be influenced. Thus, today’s science is much more transparent, and we can (and should) look at conflicts of interest in papers. They can bias results and should be taken seriously. That said, you need to actually look for conflicts of interest (rather than assuming they exist), and they should make you more cautious, but depending on the nature of the conflict, generally are not grounds for automatic dismissal of the paper.

Second, the scientific world has grown massively since the early to mid-20th century. Unlike tobacco where the debate centered around a handful of fairly small studies, topics like vaccines have thousands of studies conducted by tens of thousands of scientists from all over the world. The number of institutions and scientists working today make it unthinkable that a company could buy a consensus. In the modern world, hundreds of papers are published daily. It’s just not possible for a company to fundamentally shift that volume of literature.

Likewise, the strength of evidence presented in today’s studies massively overshadows the evidence for or against smoking available prior to the 1960s. Look at the studies I presented in this post on vaccines and autism, for example. We have multiple massive case-controlled studies, multiple cohort studies with over 100,000 children, and even a meta-analysis with over 1.2 million children. Tobacco companies were never able to get anything even approaching the type of agreement or strength of evidence.

To be 100% clear, I totally agree that modern companies are corrupt and would happily lie to the public and fund favorable studies, but topics like vaccines and climate change are supported by such a massive volume of high-quality, international research (much of which had no conflicts of interest) that it is unthinkable that companies have secretly bought nearly all the world’s scientists and thoroughly corrupted the entire body of literature. You would need some extremely strong evidence of such extensive corruption, and no such evidence exists. Further, if you think that all science is “sold to the highest bidder,” then why did tobacco companies ultimately fail? If they could not buy a consensus at a time when there were far fewer scientists and ethical standards and transparency were far looser, then why would you think that modern companies have succeeded?

Finally, I want to reiterate one of my most frequent points on this blog: do not cherry-pick studies or experts. On literally any well-studied topic, you can find a handful of outlier studies and experts. Don’t blindly believe them. Be critical and look at the entire body of evidence.

Conclusion

The true history of smoking provides a compelling example of why science is so important and why we should trust scientific results rather than anecdotes, appeals to antiquity, and appeals to nature. The latter brought us thousands of years of thinking smoking was safe and even beneficial. Science was the thing that finally showed us it was dangerous. Further, the scientific evidence was consistent from the outset. There was never a consensus of experts or evidence that smoking was safe. Yes, there was a period where most doctors and scientists smoked due to a lack of evidence regarding safety, but a lack of evidence either way is a very different thing from a large body of evidence showing that smoking is safe. Similarly, yes, tobacco companies tried very hard to deceive the public, buy off scientists, and prevent the dangers of smoking from being known, but they ultimately failed. They were never able to buy a scientific consensus. In short, tobacco companies had a good ad campaign, not a consensus, and once solid evidence of the harm from smoking started to emerge, they were powerless to prevent studies from being published. Scientists debated the evidence and kept conducting studies until a clear consensus of evidence emerged. That’s how science works and why it is so important to follow scientific evidence.

Related posts

- 5 reasons why anecdotes are totally worthless

- Ancient knowledge and the test of time

- “But scientists have been wrong in the past…”

- Most scientific studies are wrong, but that doesn’t mean what you think it means

- No one thought that Galileo was crazy, and everyone in Columbus’s day knew that the earth was round

Literature cited

- Doll. 1998. Uncovering the effects of smoking: historical perspective. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 7:87-117

- Doll and Hill. 1950. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung. Preliminary report. British Medical Journal 2: 739-748.

- Doll and Hill. 1954. The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. A preliminary report. British Medical Journal 1:1451-1455.

- Jackler and Samji. 2012. The Price Paid: Manipulation of Otolaryngologists by the Tobacco Industry to Obfuscate the Emerging Truth That Smoking Causes Cancer. Laryngoscope 122:75-87

- Hammond and Horn. 1954. The relationship between human smoking habits and death rates: a follow-up study of 187,766 men. Journal of the American Medical Association 155: 1316-1328.

- Levin et al. 1950. Cancer and tobacco smoking. A preliminary report. Journal of the American Medical Association 143: 336-338.

- Mills and Porter. 1950. Tobacco smoking habits and cancer of the mouth and respiratory system. Cancer Research 10:539-542.

- Schrek et al. 1950. Tobacco smoking as an etiologic factor in disease. Cancer Research 10: 49-58.

- Wynder and Graham 1950. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchogenic carcinoma. Journal of the American Medical Association 143: 329-336.

Just discovered your blog not too long ago, wish you had a discussion board or some wider forum as I find logic and the research world interesting. I think to the layperson most research is this broad array of anything and it’s not easily explained which journals are more reputable with higher standards versus any study that can be published by anyone. There are huge databases with different statistical methods, and then meta-studies of the totality of different studies with the effects on top of them. I haven’t come across a lot of entry points for those not already in research to parse them, much less holistically apply the information to practical knowledge.

There’s also the little problem to deal with that we’re all humans and the backfire effect is just as real as anything else. Dealing with others and trying to prove them incorrect in their thinking typically has them doubling down even when they are proven wrong, because they feel they’re being attacked or they have merged their identity with a belief. I guess I try to apply analogies to the things that are scientifically accepted to what people do in normal life to question why they are fine with one thing and not another.

On cigarettes, lets just assume someone is stuck in early radio and TV advertising and thinks its fine – does it help them in any way to spend $10 a pack nowadays even if it does nothing? Would they spend $10 on air? On vaccines, if people are so concerned about the effects of what goes in their body, why are the same people so lax about stopping at McDonald’s and grabbing a burger with who-knows-what in it made by who-knows-who? Or even better, when many get sick from a disease they didn’t believe vaccines don’t prevent, why go to the hospital or doctor, or take medicine at all? And on climate change, even if one doesn’t believe (or frankly doesn’t care) about what happens – does anyone enjoy smog in the atmosphere regardless?

I find a belief deconstructed to first principals is more effective at changing minds. In the end, if you go from ‘why should I believe ______’ you end up with a type of solipsism where other things created by science and engineers people accept everyday could just as well be questioned – so who’s to believe anything? Who’s to say the rafter in the ceiling of whatever structure one is in during the day won’t collapse randomly? There have been structural failures before – like the Kansas City Hyatt tragedy. Who’s to say the combustion engine of the vehicle you start every day or some other component won’t explode or fail? There’s been hundreds of deaths and recalls throughout automobile history.

I think it’s important to expose fallacies so I find the columns you’ve created here interesting, even if there’s the backfire effect. I also think comparing what people take for granted anecdotally on a daily basis to what they question is effective as well because its exposing that they’re tying their obstinate attitudes to something other than logic.

To exist in society everyone must trust an interaction with something they don’t have direct expertise over as safe and more often than not what is labeled as true or not true depends on many other factors than logical thinking.

LikeLike