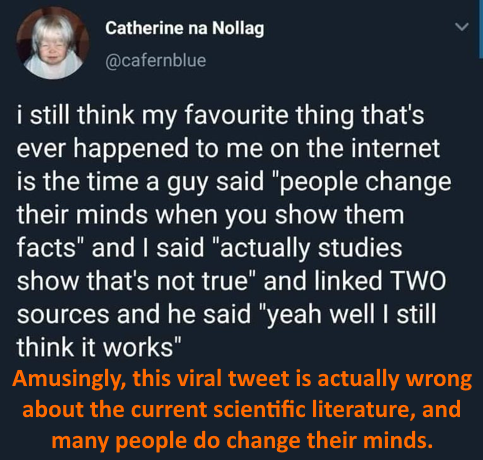

The “backfire effect” is a psychological phenomenon in which correcting misinformation actually reinforces the false view rather than causing someone to reject it (Nyhan and Reifler 2010). This topic comes a lot in the comments on this and other pro-science pages. Sometimes it is presented as an argument that pages like this one actually do more harm than good, and other times it is brought up as a general point about how difficult it is to change people’s minds. Most of the commentary I see around this topic is, however, misleading at best. Ironically, many of the statements I see about the backfire effect are actually misinformation. The evidence for the backfire effect is actually pretty weak and mixed, and it may not even be a real effect at all. If it is a real effect, it is pretty clear at this point that it is not a wide-spread, generalizable effect that occurs anytime misinformation is corrected. So, in this post, let’s dig into the literature and see what the current state of evidence actually looks like.

The “backfire effect” is a psychological phenomenon in which correcting misinformation actually reinforces the false view rather than causing someone to reject it (Nyhan and Reifler 2010). This topic comes a lot in the comments on this and other pro-science pages. Sometimes it is presented as an argument that pages like this one actually do more harm than good, and other times it is brought up as a general point about how difficult it is to change people’s minds. Most of the commentary I see around this topic is, however, misleading at best. Ironically, many of the statements I see about the backfire effect are actually misinformation. The evidence for the backfire effect is actually pretty weak and mixed, and it may not even be a real effect at all. If it is a real effect, it is pretty clear at this point that it is not a wide-spread, generalizable effect that occurs anytime misinformation is corrected. So, in this post, let’s dig into the literature and see what the current state of evidence actually looks like.

Backfire effects are not widespread

The first critical point that many get wrong is that the data have never suggested that backfire effects are a widespread issue that happen anytime misinformation is corrected. A lot of times when I see people bringing up this topic, they act as if backfire effects are inevitable anytime you correct misinformation on any topic for any group of people. In reality, the studies documenting backfire effects have always found that they only apply to subgroups and certain topics. Indeed, the first study on backfire effects (Nyhan and Reifler 2010) only found them in 2 of the 5 topics they tested, and several years later, one of the original authors wrote an article (Nyhan 2021) in which they tried to set the record straight and bemoaned the fact that many media outlets had mischaracterized backfire effects and treated them as the dominant reason for the persistence of political misinformation.

To quote one of the original authors (Nyhan 2021),

“subsequent research suggests that backfire effects are extremely rare in practice”

Backfire effects have low reproducibility

If you read this blog often, you know that I spend a lot of time talking about the importance of looking for consistent evidence. There are publication biases towards positive results, a lot of low-quality papers do get published, and even for a perfectly conducted study, you may get a false positive just by chance. As a result, on essentially any topic, you can find papers arguing for it and papers arguing against it. Therefore, you should not cherry-pick studies and should instead look for a consensus of evidence. If an effect is real, studies should be able to document it with a reasonable degree of consistency. When it comes to backfire effects, the results are highly inconsistent.

There is a really interesting review on backfire effects that I highly recommend reading (Swire-Thompson et al. 2020). They found that, although this field looked really promising at first, a huge number of studies have failed to find evidence of the backfire effect, even when trying to directly replicate previous studies. For examples, see: Cameron et al. 2013; Garrett et al. 2013; Weeks & Garrett, 2014; Weeks, 2015; Ecker et al., 2017; Haglin, 2017; Swire, et al. 2017; Guess & Coppock, 2018; Nyhan et al., 2019; Schmid & Betsch, 2019; Swire-Thompson et al., 2019; Wood & Porter, 2019; Ecker et al. 2020; Ecker et al. 2021; Ecker et al. 2023. This lack of consistency occurs even in the subgroups/topics where researchers initially thought there were real backfire effects (also note that the authors of the original paper on backfire effects are authors on several of these papers that failed to find backfire effects).

In one of the largest and most comprehensive studies of this topic, scientists conducted five trails designed to approach the problem from slightly different ways. The trials covered a total 52 statements/corrections and included a total of 10,100 participants (Wood & Porter, 2019). They were not able to elicit a backfire effect for a single one of those 52 statements/corrections! Indeed, as with many of these studies, they found that correcting the misinformation resulted in an average improvement in scores. In other words, people updated their knowledge with the new information, and on average, their answers were more correct after the misinformation had been corrected (the opposite of a backfire effect).

All of this makes me extremely dubious about the backfire effect. If the effect is real, it should be reproducible, yet over and over again, the largest studies and replication studies fail to document backfire effects. So, let’s look closer at some of the factors that are going on here.

Study quality

One of the other things I talk about a lot is that study quality can vary slightly, and very often for topics where there is no effect, there is a negative correlation between study quality and the statistical significance of the outcomes. In other words, lower quality studies tend to produce positive results, but those effects disappear with larger, better controlled studies. This at least partially seems to be the case for backfire effects. As mentioned earlier, some of the largest studies (e.g., Wood & Porter, 2019) failed to find a backfire effect, but there is also an interesting trend when we look at response “reliability.”

Basically, “reliability” refers to whether studies are using questions that will give consistent results. In the Swire-Thompson et al. (2020) review, they pointed out that using only a single measure of agreement with a statement is often unreliable and can lead to false positives, and 81% of reported backfire effects relied on only a single measure. This suggests a large opportunity for false positives and raises serious questions about the majority of studies documenting backfire effects.

Swire-Thompson et al. (2022) took this further with a really elegant study that I recommend reading. In short, they used a test-retest procedure where they randomly split participants into treatment and control groups. The treatment groups where shown incorrect statements and asked to rate the truth of the statement. Then they were shown corrections to the statement. Then they were retested three weeks later. Thus, if the backfire effect was occurring, they should rate the false statements as more true, on average, on the second test. The control group underwent the same procedure except they were not shown the corrections. This is a great design, because it let the authors use the control group to look at how reliable responses were across the 21 statements they used. They also ran the study twice to ensure results were repeatable (once with 388 participants and once with 532 participants).

There are a bunch of interesting results to this study (only some of which I have time to cover here). First, on average, the treatment group that was shown corrections updated their views more than the control group that was not shown corrections. In other words, again, the average effect was that people updated their views when shown fact checks (the opposite of a backfire effect). Second, in the treatment group, only 2 of the 21 statements showed any sign of a backfire effect (i.e., on average, people rated the false statement as more true after being shown the correct information), but neither was statistically significant. In other words, out of 21 tests across two trials, they did not elicit a single statistically significant backfire effect.

Taking this a step further, things get really interesting when we start looking closer at the patterns for the individuals who “backfired.” In other words, even though on average there was no backfire effect, there were some individuals whose scores suggested that they were more convinced of the false information after seeing the correction. This is where those reliability scores from earlier come in. Using the control group, the authors were able to measure the reliability of responses for each of the 21 statements, then look at how those reliability scores correlated with the level of backfiring in the treatment group. In other words, they used the control group (which was not shown fact checks) to see how consistently people rated the truth of each false statement, then they checked whether questions with a low consistency of responses in control group were more likely to have backfires in the treatment group. That is, in fact, exactly what they found: there was a strong negative correlation. In other words, the less reliable (repeatable) the responses to a statement were, the stronger the backfire “effect” was, thus strongly suggesting that measurement error is a big factor in studies reporting backfire effects. Indeed, in the two trials in this study, 37% and 53% of the variation in backfire effects was explained by the repeatability measures. That’s massive and provides a very plausible source of false positives in the broader literature.

The average effect of correcting misinformation is positive

Finally, it is worth explicitly pointing out that most of the studies I’ve been discussing have not only failed to find a backfire effect, but they have actually found a net improvement in scores after correcting the misinformation. In other words, the average effect of presenting fact checks is an improvement in peoples’ knowledge.

To again quote one of the researchers who originally described the backfire effect (Nyhan 2021),

“[There is an] emerging consensus that exposure to corrective information typically generates modest but significant improvements in belief accuracy.”

and

“Contrary to media coverage of the backfire effect, subsequent research finds that people are often willing to revise mistaken beliefs when given accurate information.”

With that said, there is an important caveat. Saying that “the average effect is an improvement in belief accuracy” is not the same thing as saying “the average person will improve their belief accuracy.” In other words, these studies look at group effects, which don’t necessarily give a good reflection of what an average individual does.

As a hypothetical example, imagine we have a group of 100 people who believe the moon landing was fake, then we show them a fact check and 70 people remain unchanged, 20 update their views and accept the moon landing was real, and 10 dig in their heals and become more convinced it was fake. In that situation, the average score for the group as a whole will go up, showing that correcting the misinformation has a net benefit, but most individuals (70%) did not update their views, and a handful backfired (10%).

So, the key questions become, why did so few update their views, and where those 10 “backfires” measurement errors, or did encountering corrective information really make them more convinced of the false information (a true backfire)? Moving away from these group level effects and trying to understand factors for individuals is a promising approach and seems to be where the field is likely shifting.

Conclusion

So where does all of this leave the backfire effect? In short, to a large extent, it does not appear to be a real thing. It has never been generalizable, and it has only ever showed up for subgroups, but even for those subgroups, studies reporting backfire effects often can’t be replicated, numerous large, well-conducted studies have failed to find backfire effects, and the weight of evidence shows that the average effect of correcting misinformation is an improvement in the accuracy of peoples’ views (the opposite of a backfire effect). Further, studies reporting backfire effects often have low quality, and research has shown that a large portion of reported backfire effects are likely false positives due to low reliability of the questions being asked. So, if the backfire effect is real, it is very rare and is probably related to very specific individual-level traits that are not currently well understood.

Therefore, the backfire effect should not be used as a reason for not correcting false information. The data show that, on average, fact checks do more good than harm.

Literature cited

- Cameron et al. 2013. Patient knowledge and recall of health information following exposure to “facts and myths” message format variations Patient Education and Counseling 92:381-387

- Ecker et al. 2017. Reminders and repetition of misinformation: Helping or hindering its retraction? Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6:185-192

- Ecker et al. 2020. Can corrections spread misinformation to new audiences? Testing for the elusive familiarity backfire effect. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 5:41

- Ecker et al. 2021. Corrections of political misinformation: no evidence for an effect of partisan worldview in a US convenience sample. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 376:20200145.

- Ecker et al. 2023. Correcting vaccine misinformation: A failure to replicate familiarity or fear-driven backfire effects. PLoS ONE. 18(4): e0281140.

- Garrett et al. 2013. Undermining the corrective effects of media-based political fact checking? The role of contextual cues and naïve theory. Journal of Communication, 63:617-637

- Guess and Coppock. 2018. Does counter-attitudinal information cause backlash? Results from three large survey experiments. British Journal of Political Science 2018:1-19

- Haglin. 2017. The limitations of the backfire effect. Research & Politics 4.

- Nyhan and Reifler. 2010. When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Polit. Behav. 32:303–330

- Nyhan 2021. Why the backfire effect does not explain the durability of political misperceptions. PNAS 118:e1912440117

- Nyhan et al., 2019. Taking fact-checks literally but not seriously? The effects of journalistic fact-checking on factual beliefs and candidate favorability. Political Behavior 2019:1-22

- Schmid & Betsch. 2019. Effective strategies for rebutting science denialism in public

- discussions. Nature Human Behaviour, 1

- Swire, et al. 2017. Processing political misinformation: Comprehending the Trump phenomenon. Royal Society Open Science 4

- Swire-Thompson et al., 2019. They might be a liar but they’re my liar: Source evaluation and the prevalence of misinformation. Political Psychology 41: 21-34

- Weeks, 2015. Emotions, partisanship, and misperceptions: How anger and anxiety moderate the effect of partisan bias on susceptibility to political misinformation. Journal of Communication 65:699-719

- Weeks and Garrett, 2014. Electoral consequences of political rumors: Motivated reasoning, candidate rumors, and vote choice during the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 26:401-422

- Wood and Porter. 2019. The Elusive Backfire Effect: Mass Attitudes’ Steadfast Factual Adherence. Political Behavior 41:135–163

I think that one has to consider how emotionally invested a person has in a particular belief. If a scientist learns that a theory he has accepted for many years has been proven wrong by new evidence, he is going to take that in stride. If you try to convince a devout member of a religion that their belief is wrong, that is a different thing because the whole structure of their life is based around their belief. Changing would drastically affect their personal and social relationships and the activities they take part in regularly.

LikeLike

Several studies have looked at this sort of thing. Results are somewhat mixed, but there is no clear evidence that it makes a difference (which honestly surprised me when I started looking into this) Swire-Thompson et al. (2022)

LikeLike

I think that one has to consider how emotionally invested a person has in a particular belief. If a scientist learns that a theory he has accepted for many years has been proven wrong by new evidence, he is going to take that in stride. If you try to convince a devout member of a religion that their belief is wrong, that is a different thing because the whole structure of their life is based around their belief. Changing would drastically affect their personal and social relationships and the activities they take part in regularly.

LikeLike

Thank you for all this interesting information. What you say “If the effect is real, it should be reproducible, yet over and over again, the largest studies and replication studies fail to document backfire effects.”…”The average effect was that people updated their views when shown fact”…”Therefore, the backfire effect should not be used as a reason for not correcting false information.” it all make sense to me and you provide evidence.I should say that based on personal experience (I know personal anecdotes is not scientific evidence) I’ve seen that emotional attachment can cause a short lived sort of backfire effect, or an emotional reaction. Using myself as an example. In the past I used to read mostly rightwing publications including some with conspiracy theories, such as world net daily. I thought that climate change was mostly bunk. I knew CO2 was a greenhouse gas, but I did not think it could cause any significant global warming. It was leftwing group think and bias. When someone tried to correct my misconceptions, I dug in. It was an emotional reaction.

However, after some time I decided to look at the facts a bit closer. After all the people who corrected my misconceptions made sense and I did know much about the topic. So, I took a deep dive into the subject, and I found out I was completely wrong. I had been bamboozled. It probably helped that I had a degree in Electrical Engineer and Physics, but even with that education politics had caused me to jump the gun, well up until that point. I think that sometimes people can dig in as an emotional reaction but that in the long run politely correcting misconceptions will help. I should say I think correcting false information politely is important. At least I don’t listen to people who are rude to me. Anyway, that’s why I’ve been suspicious of the backfire effect. Having that confirmed by your scientific analysis is nice. I later joined an organization called Citizens Climate Lobby to advocate for climate solutions.

LikeLike

If I say I don’t believe this is the case, am I making a self fulfilling prophecy that the information about this backfired? Hmm .. 😛

I will say there are probably some important distinctions about these studies. First, what is the subject matter and what pool of people are the sample size coming from? I would imagine a 50 year old from rural Alabama who watches FOX News every night and trolls on social media isn’t apt to sign up for a study.

Also, tribalism plays a big role, also as ‘acitta’ above mentioned it ties into how emotionally invested the person is in being right. Climate change has been politicized and tied to a person’s identity. And not only that, people are more apt to make excuses for their life decisions by saying something isn’t true rather than just owning what they’re doing.

People want to use fossil fuels because its cheaper right now, they don’t want to be inconvenienced, pay more, or have their choices questions at an ethical level of its impact on society. Saying its a hoax and climate change doesn’t exist is an easy out of those situations and it becomes politicized.

If you live in the US, this is part of capitalism: investments are touted as being smart rather than exploitation of labor and consumers by taking the overhead for personal gain. Industrialization and consumption are treated almost as charity: if you’re a billionaire and burning fossil fuels going on a private jet to a private island and going yachting, its all treated as this warped version of benevolence – see all the jobs created for planes, pilots, boats, oil drilling for my personal enjoyment? Many people don’t WANT to think about the impact they have on society, earth, others in the present or the future so the ‘out’ is denial.

The simple way out of handing that dissonance is to just say climate change doesn’t exist, find fringe science to support it, say its a big conspiracy to ruin progress, etc. I don’t think these types of people are saveable via providing correct information, there’s so many people who simply psychologically addicted to doing that they don’t WANT to change their behavior but they also don’t want to lay claim to what they’re doing is unethical or any friction for their behavior. The answer to that is denial to protect their ego.

LikeLike

Many of the studies have looked at factors such as age and political ideology, as well as using a range of different topics for the fact statements. Early on, it looked like backfire effects were limited to particular subgroups/topics, but replicating those results has proved problematic. Basically, no matter how you split the data, studies have not been able to reliably replicated the backfire effect.

LikeLike