Lately, my Facebook page has been flooded with people insisting that “no vaccine is tested against a placebo” (sometimes stated with additional qualifiers like “double-blind” or “saline placebo”). This claim, like so many anti-vaccer claims, is blatantly false. Nevertheless, I think it is worth looking at it more closely to better understand the tools available to scientists, the information they provide, and which tools to use for which applications. People often act as if randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) are the one and only valid scientific approach and no other study design is even worth considering. In reality, placebo-controlled trials are great for certain applications, but they are far from the only useful approach, and in many cases, they are actually a highly inappropriate method.

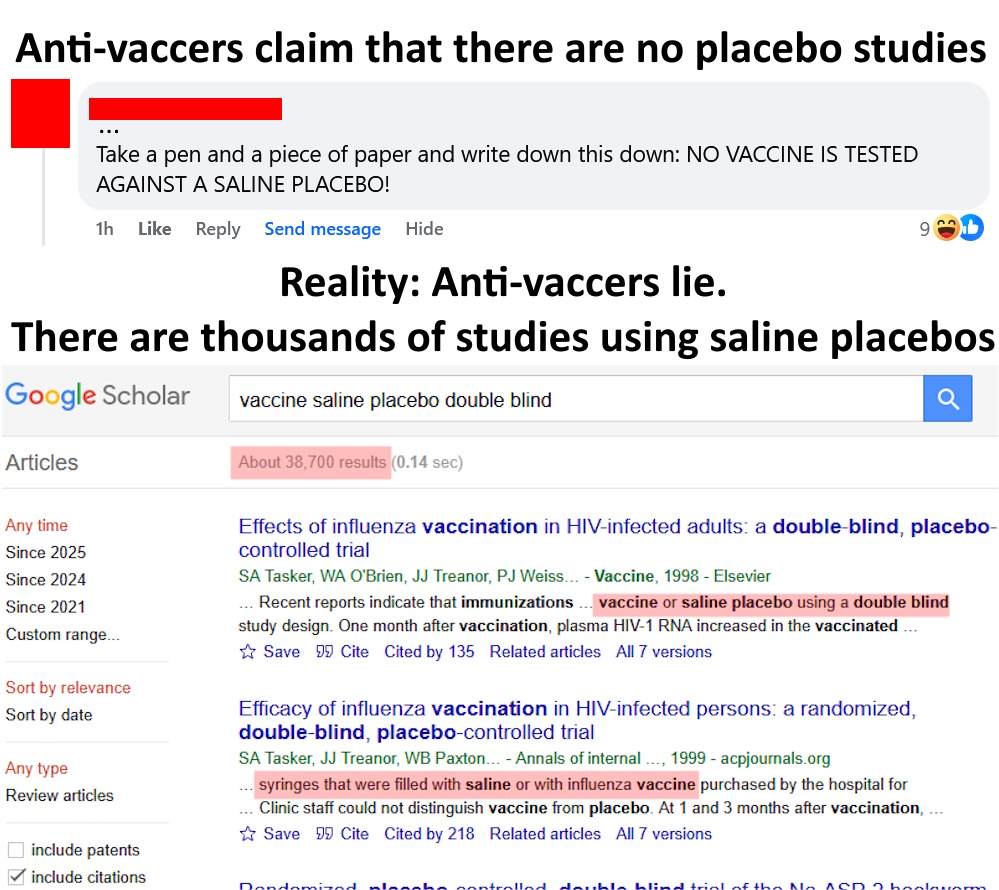

Vaccines are tested against placebos (including saline placebos)

It is simply not true that vaccines aren’t tested against placebos (including inert saline placebos). Anyone who says otherwise is either lying or willfully ignorant. Don’t take my word for it, go to Google Scholar or PubMed or any other scientific database with medical research and do searches like, “saline placebo double blind vaccine” and you will find literally thousands of papers. This sort of testing is standard as part of Phase II and Phase III clinical trials. Vaccines routinely go through RCTs before being released to the public (including COVID vaccines, btw, e.g., this RCT on Pfizer’s vaccine [BNT162b2; Thomas et al. 2020] or this RCT on Moderna’s vaccine [mRNA-1273; Baden et al. 2021], both of which used saline placebos).

It’s also worth briefly noting that among those studies you will find numerous trials where the vaccine either did not work or had serious side effects and, therefore, never went to market. Vaccines are stringently tested and ones that don’t pass those tests are either scrapped or modified then retested.

Other types of controls

Although clinical trials do generally use inert, saline placebos, there certainly are some studies that either use an older version of the vaccine or the vaccine’s adjuvants as the control (“placebo”). There are usually very good reasons for this, so let’s talk about them.

Let’s start with why scientists might use an older version of a vaccine as a control rather than an inert saline placebo. I’d like to begin with an analogy. Imagine you are a seat belt manufacturer, and you have developed a new seat belt design that you want to test. What would be the best control for those tests: no seat belt at all or the current standard seat belt design? Obviously comparing it against the current standard design makes more sense, right? You already know that the current design works. You already know its safety profile. You already know the level of protection it provides and how often it ends up injuring someone (seat belts aren’t 100% safe or effective after all). So, the relevant question is not, “how safe and effective is the new design compared to nothing?” The question is, “how safe and effective is the new design compared to the current standard design?”

The same situation is true for vaccines. If you develop a new version of a given vaccine, it may make more sense to simply compare it to the current standard of that vaccine which already has a known safety profile and level of effectiveness, rather than comparing it to a placebo (this is especially relevant given the ethical issues that we’ll get to in a minute).

Using adjuvants as the control group often occurs for similar reasons. Namely, it lets scientists isolate the effects of the active components of the vaccine compared to the adjuvants. This is useful both because the adjuvants have generally already been tested and have known safety profiles and because it means that if problems arise in the vaccine group, then scientists can narrow down which part of the vaccine is causing the problem and make appropriate changes.

I say this a lot on this blog, but scientists aren’t stupid. They spend a lot of time thinking about experimental designs and their designs have to pass the approval of ethics committees before proceeding. They try very hard to ensure they are using the best design possible to answer the question at hand. So, when you see something like a trial that used an adjuvant rather than an inert placebo, don’t throw up your hands and assert that the research is all nonsense. Rather, take time to carefully look at the study. Read the authors’ justification for the design, and look at how it fits into the broader literature. There’s likely a good reason for the study’s design.

Ethical issues with placebo-controlled trials

Despite everything that I have said so far, it is true that after the initial clinical trials, most follow-up studies on vaccines are not placebo-controlled, and there are several important reasons for this. One of the biggest is simply ethics.

Once a vaccine has been demonstrated to be safe and effective, it becomes highly unethical to do a double-blinded placebo-controlled trial where you are leaving half the participants (often children) vulnerable to diseases that you know you could prevent. It is totally unethical to play Russian Roulette with their lives. Despite what anti-vaccers like to claim, the benefits of vaccines are so extraordinary and so well documented that it is unethical to withhold them for an experiment.

Fortunately, scientists have other tools they can use, many of which are actually better than RCTs when it comes to detecting the conditions that people are often concerned about (e.g., autism).

Other useful study designs

Beyond the ethical issues, placebo-controlled trials are also problematic because they are expensive to run, difficult to maintain adequate controls over long periods, and are data hungry when it comes to rare events. That last point is the one that I really want to focus on here.

Sample size is obviously important in research, and the rarer the effect, the larger the sample size needs to be, but that quickly becomes a problem with RCTs. Imagine, for example, that an outcome in question has a background rate of 1 in 1000 and the drug being tested increases that rate to 2 in 1000. How big of a sample size do you need to detect that increase that with an RCT? Even without getting into the mathematical details, you should easily be able to convince yourself that it is going to require a rather massive data set to detect such a rare event. Even at 10,000 participants in each group (a truly enormous RCT) you’d only expect 5 positive cases in the control group and 10 in the drug group. That’s not a very big difference.

So, in those cases, a much better design is often what is called a case-controlled design. I explained this in more detail here, but essentially, what it does is flip the study design so that you start with a group of people with the outcome of interest (e.g., autism), match them with a group of people that is similar except that they lack that outcome of interest (e.g., don’t have autism), then you work backwards to look for the potential cause of interest (e.g., difference in vaccination rates between the two groups). This study design is great for rare conditions because you start with that rare outcome, rather than starting with a huge number of people and waiting to see if some eventually develop it. So even if the outcome only occurs in 1 in 100,000 people, you may be able to find enough medical records to let you do a meaningful study. Even a few hundred participants can be quite powerful for this design, whereas a few hundred people would be utterly meaningless in an RCT for rare conditions.

Although not the point of this post, I’ll note that this design has repeatedly been used to study vaccines and autism, often with large samples sizes, and the result has consistently been that vaccines do not cause autism (e.g., Destefano et al. 2004; Smeeth et al. 2004; DeStefano et al. 2013; Uno et al. 2015)

Now, you may be thinking, “but vaccines cause wide-spread harm, not rare occurrences!” In which case, you’re wrong, but, more importantly, we have a better design for more common conditions. Namely, a retrospective cohort study. Again, more details here, but in brief, this design generally follows more of the “standard” experimental approach, but it uses medical records, rather than actually giving patients anything (thus avoiding the ethical issues). So, you can look through medical records to, for example, categorize people into groups that did or did not receive a given vaccine (but are otherwise similar) then look at the proportions in each group that developed an outcome of interest (e.g., autism). The big advantages here are that you don’t have the ethical issues, the cost is lower than RCTs, and you don’t have to personally follow patients for years. As a result, you can achieve massive sample sizes of tens or even hundreds of thousands of participants, something that is almost never possible in RCTs. So, this design can be much more powerful than an RCT (for certain questions) simply because of the enormous sample sizes it allows.

Once again, several massive cohort studies have looked at vaccines and autism and consistently found that there is no association (e.g., Hviid et al. 2019; Madsen et al. 2002; Anders et al. 2004; Jain et al. 2015)

A lack of correlation is generally a lack of causation/you don’t always need placebos

There is one more critical topic that needs to be discussed here. Namely, study designs like cohort studies and case-controlled studies are much better at showing a lack of effect than they are at showing causation.

Causation is a hard thing to demonstrate (something anti-vaccers don’t seem to grasp). To confirm it, you need to not simply show that two things change together (i.e., are correlated), but rather that nothing other than causation can explain that correlation. This is the beauty of a randomized placebo-controlled design and why it is the “gold standard” for testing effectiveness. By randomizing the treatment across patients and administering a placebo (plus careful statistical analysis), you can control confounding factors so that you can be confident that the changes you see in the treatment group are being caused by the experimental factor rather than simply being associated with it. RCTs are, in most cases, the best way to establish causation (at least for topics like medicine).

Because they do not randomize and do not include placebo controls, case-controlled studies and cohort studies generally struggle to demonstrate causation. If they were able to very carefully match their participants and include appropriate covariates in their models, they may be able to strongly suggest a causal relationship, but there are serious limits to their interpretation. They are, however, great at establishing safety, because while correlation does not automatically indicate causation, a lack of correlation does generally indicate a lack of causation.

To understand what I mean, we need to talk about causation just a little bit further. Imagine that you show that X is positively correlated with Y. So, when X goes up, Y also goes up. Does X cause Y? Maybe, but it could also be that Y causes X or that some other variable is causing both X and Y. You’d need an RCT to tease that out.

However, suppose that X and Y are not correlated. So changes in X do not correspond to changes in Y. Does X cause Y? No. It’s an easy answer. At least within the statistical limits of the study in question, if changes in X don’t result in changes in Y, then X doesn’t cause Y.

What this means is that when large cohort and case-controlled studies find a total lack of association between vaccines and something like autism, that is actually really good evidence that vaccines don’t cause autism. Think of it this way, how could vaccines be causing autism if the group that received that vaccines doesn’t have higher autism rates than the group that did not receive the vaccine? (again assuming appropriate statistical design, case-matching, and within the confidence limits of the study)

To put that another way, if you are one of the people who likes to harp on the supposed lack of placebo-controlled vaccine trials (again, the do actually exist), then I want you to look at the large cohort studies and tell me exactly how you think a placebo would have made a difference. Look at studies like Madsen et al. (2002), which looked at records for 440,655 children who received an MMR vaccine and 96,648 children who did not receive an NMR vaccine, then compared their rates of autism (they were not statistically different). Exactly how do you think things would have been different if the people in the unvaccinated group had received a placebo instead of simply not being vaccinated. Do you think the placebo would magically have prevented them from developing autism? What would that have changed? A lack of placebo is simply not a valid criticism for this sort of study. If people who received the vaccine didn’t experience higher rates of autism, then that is good evidence that the vaccine doesn’t cause autism.

“But what about the entire vaccine schedule!?”

Finally, one last specific criticism I sometimes here is, “sure, individual vaccines were tested against a placebo, but no one has ever done a placebo-controlled trial on the entire vaccine schedule.” For once, that claim is at least true (to the best of my knowledge), but it is also a meaningless demand for an impossible test. That test would be completely unethical and also extremely difficult to pull off. It’s just not a plausible experiment.

There are, however, other approaches that scientists have used. For example, there is this massive cohort study of almost a million children that looked at numerous combinations of vaccines, comparing them to single vaccines (Bauwens et al. 2022). There are also studies that looked at the effects of antigen load (i.e., the number of antigens children are exposed to from vaccines; DeStefano et al. 2013; Iqbal et al. 2013; DeStefano et al. 2013). Other studies have looked at adding vaccines to the schedule or the effects of vaccines given together or spaced out (Olivier et al. 2008; Arguedas et al. 2010; Vesikari et al. 2010). All of these are different ways to examine combinations of vaccines.

Additionally, based on everything we know about vaccines (including studies like the ones cited above), there is simply no reason to expect serious harm from the routine schedule, and no matter how thoroughly something has been tested, there will always be things that haven’t been tested.

Imagine, for example, that someone actually did manage to do an RCT on the whole schedule and found a lack of significant side effects, anti-vaccers could then respond (and likely would respond) with things like, “well what about the whole schedule + GMOs, or the whole schedule while taking aspirin, or the whole schedule while watching 10 hours a week of TV” etc. There are endless possibilities, most of which are utter nonsense.

Don’t get me wrong, when actual serious, plausible concerns arise, scientists should (and do) take that seriously and test accordingly, but that’s simply not the case with these arguments about vaccines and placebo-controlled trials. Likewise, just to be 100% clear, there are side effects from vaccines (just like all real medicines). No one is saying that they are 100% safe, but they are very well-tested and serious side effects are extremely rare. Nevertheless, I (and all scientists) welcome improvements in vaccines to make them even safer. Unfortunately, instead of perusing those improvements, we are left doing things like looking at vaccines and autism for the 100th time as if one more study will somehow make a difference.

Statistical note: Throughout, you may have noticed that I use phrases like “within the statistical limits.” This is an important, albeit somewhat technical, caveat. In brief, it is never possible to prove a negative. There are several reasons for this, but the most important for the topic at hand is that it is always possible that there is an effect, but it occurs rarely enough that you were not able to detect it with the current sample size. So even if you have a sample size of several million participants, you aren’t going to detect something that occurs once every billion patients. So you can never, for any treatment, say with 100% certainty that there is no effect. However, if with large enough studies and proper statistics and designs (as has been done for vaccines and autism), you can confidently state that if there is an effect, it is so extraordinarily rare that for all intents and purposes, there is no effect. Stated another way, for something like vaccines and autism, we are as close to being able to state that “vaccines do not cause autism” as we are ever going to be. We have used so many giant studies, that we can state that if vaccines cause autism, it is such an extremely rare side effect that it is statistically undetectable.

Related posts

- Vaccines and autism: A thorough review of the evidence (2019 update)

- Why are there so many reports of autism following vaccination? A mathematical assessment

- When is it reasonable to demand more studies?

- Methodolatry: An over-reliance on placebo-controlled trials

- The hierarchy of evidence: Is the study’s design robust?

Literature cited

- Anders et al. 2004. Thimerosal exposure in infants and developmental disorders: a retrospective cohort study in the United Kingdom does not support a causal association. Pediatrics 114:584–591

- Arguedas et al. 2010. Safety and immunogenicity of one dose of MenACWY-CRM, an investigational quadrivalent meningococcal glycoconjugate vaccine, when administered to adolescents concomitantly or sequentially with Tdap and HPV vaccines. Vaccine 28:3171-3179

- Baden et al. 2021. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 384:403–416

- Bauwens et al. 2022. Safety of routine childhood vaccine coadministration versus separate vaccination. BMJ 7

- DeStefano et al. 2004. Age at first measles-mumps-rubella vaccination in children with autism and school-matched control subjects: a population-based study in metropolitan Atlanta. Pediatrics 113:259–266

- DeStefano et al. 2013. Increasing exposure to antibody-stimulating proteins and polysaccharides in vaccines is not associated with risk of autism. J Ped 163:561–567

- Dolhain et al. 2019. Infant vaccine co-administration: review of 18 years of experience with GSK’s hexavalent vaccine co-administered with routine childhood vaccines. Expert Review of Vaccines 19:419-443

- Glanz et al. 2018. Association Between Estimated Cumulative Vaccine Antigen Exposure Through the First 23 Months of Life and Non–Vaccine-Targeted Infections From 24 Through 47 Months of Age. JAMA 319:906-613

- Hviid et al. 2019. Measles, mumps, rubella vaccination and autism: A nationwide cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine.

- Iqbal et al. 2013. Number of antigens in early childhood vaccines and neuropsychological outcomes at age 7–10 years. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 22:1263-1270

- Jain et al. 2015. Autism occurrence by MMR vaccine status among US children with older siblings with and without autism. JAMA 313:1534–1540

- Madsen et al. 2002. A population-based study of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination and autism. New England Journal of Medicine 347:1477–1482

- Olivier et al. 2008. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity, and safety of a seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) concurrently administered with a fully liquid DTPa—IPV—HBV—Hib combination vaccine in healthy infants Vaccine 26:3142-3152

- Smeeth et al. 2004. MMR vaccination and pervasive developmental disorders: a case-control study. Lancet 364:963–969

- Thomas et al. 2020. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine through 6 Months. New England Journal of Medicine 85:1761–1773

- Uno et al. 2015. Early exposure to the combined measles-mumps-rubella vaccine and thimerosal-containing vaccines and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Vaccine 33:2511–2516

- Vesikari et al. 2010. Immunogenicity and safety of the human rotavirus vaccine RotarixTM co-administered with routine infant vaccines following the vaccination schedules in Europe. Vaccine 28:5272-5279