I want to briefly discuss a logical fallacy that is surprisingly common, despite being so obviously absurd. I suspect that most people committing this fallacy do so without ever actually contemplating what they are saying, and it is my hope that discussing this fallacy will help people to both spot and avoid it.

I want to briefly discuss a logical fallacy that is surprisingly common, despite being so obviously absurd. I suspect that most people committing this fallacy do so without ever actually contemplating what they are saying, and it is my hope that discussing this fallacy will help people to both spot and avoid it.

The fallacy in question goes by many names including, argument from incredulity, personal incredulity, appeal to incredulity, appeal to personal incredulity, and argument from personal incredulity. I will simply refer to it as the incredulity fallacy.

“Incredulity” refers to an inability or unwillingness to consider the possibility of something, and the fallacy occurs when someone asserts that they are right about something because they cannot personally imagine that the alternative is true.

Stated like that, hopefully the problem is obvious. Reality is not determined by an individual’s imagination. Whether or not someone can imagine that something is true has absolutely zero bearing on whether or not it is true, and someone’s lack of imagination is not a good argument against something. Nevertheless, this argument is pervasive.

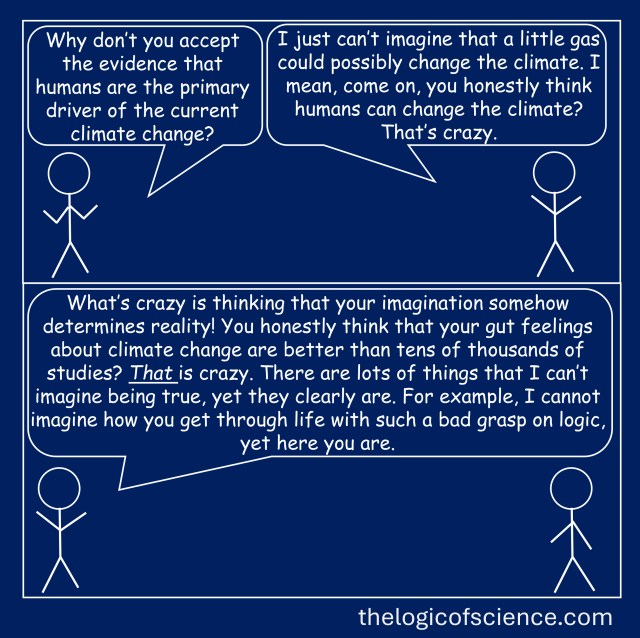

To illustrate this, I’m going to use an example that I have personally run into countless times over the past few years, and I suspect many of you have encountered it as well. The argument is from the political world, but I’m not making any political comments here. I’m just using this one particular argument to illustrate the fallacy.

I know many people, including family members, who think that Trump won the 2020 presidential election, and when I ask them why they don’t accept the results, one of the answers that I inevitably get is something along the lines of, “come on, you don’t really think that Biden got 81 million votes, do you? There’s no way 81 million people voted for Joe Biden!”

This is always stated as if it is a concrete, established fact that 81 million people could not possibly have voted for Biden. In reality, of course, it is nothing other than a self-reinforcing projection of their existing views.

We can rephrase it simply as, “I cannot personally imagine that 81 million people voted for Joe Biden, therefore it didn’t happen.”

The argument is, of course, entirely circular. We can rephrase it yet again as, “I don’t believe Joe Biden won because I don’t believe Joe Biden won.”

At no point are facts or evidence injected into the view. The view is simply stated as a fact.

While that example came from politics, this flawed reasoning also pervades anti-science arguments. For example, I have frequently encountered anti-vaccers who make statements like, “I can’t accept that injecting chemicals into an infant is good for them” or climate change deniers who say things like, “you honestly think that humans producing a little CO2 will alter the climate? lol.” These are both examples of incredulity. Just because someone doesn’t personal think “chemicals” can be good or human CO2 emissions can change the climate doesn’t mean those positions are false.

You’ll also notice that this fallacy is closely related to (and in some cases identical to) the appeal to common sense fallacy or just “gut feelings.” In all of these cases, the arguments are about what someone “feels” is true or false, not about what is actually verifiably true or false.

Going back to one of my interactions with a family member, when I pressed them on why they refused to accept that Biden won in 2020, they said, “It’s just common sense!” The problem, of course, is that “common sense” is not objective and varies from one person to another. As I pointed out to them, my “common sense” tells me that Biden won, so whose common sense should we listen to? If “common sense” is a reliable indicator of reality, then why do our “common senses” disagree with each other?

Likewise, I constantly encounter people who insist that it is just “common sense” that vaccines are dangerous, climate change isn’t being cause by humans, GMOs are dangerous, etc. Meanwhile, my “common sense” says the opposite. So, whose “common sense” is right?

This is, of course, precisely why we conduct rigorous scientific studies (and conduct elections) rather than just asking random people what they think. Sticking with the election example for a minute, if we follow these people’s arguments though to their logical conclusions, then there is no reason to hold an election. All we have to do is ask them who they think would win and we have our result. That, of course, is madness.

All of these brings me back to two central points that I make over and over again on this blog. Honestly, they are the two points at the very core of this blog’s existence.

First, fact check everything using good sources. Take nothing for granted. Verify that something is true before you believe it and verify that it is false before you reject it.

Second, be willing to be wrong. If you are someone who has made statements like the ones illustrated in this post, then really stop and think carefully about your views. Doesn’t it bother you that your argument boils down to “I’m right because I know I’m right?” Don’t you want to have a view of the world that is actually based on evidence and facts?

Always ask yourself, “what evidence would convince me that I am wrong?” If you say that nothing will convince you that you are wrong, then your position is, by definition, willfully ignorant.

Set aside your biases and preconceptions, accept the possibility that you might be wrong, and actually look at the evidence. Don’t trust your “gut instincts” or “common sense” or what you “just know.” Look at what is true, not what you want to believe is true.

Related posts